A new aerial forest fertilization project in the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District (SLRD) aims to sequester carbon dioxide in forests and improve timber volumes for harvesting.

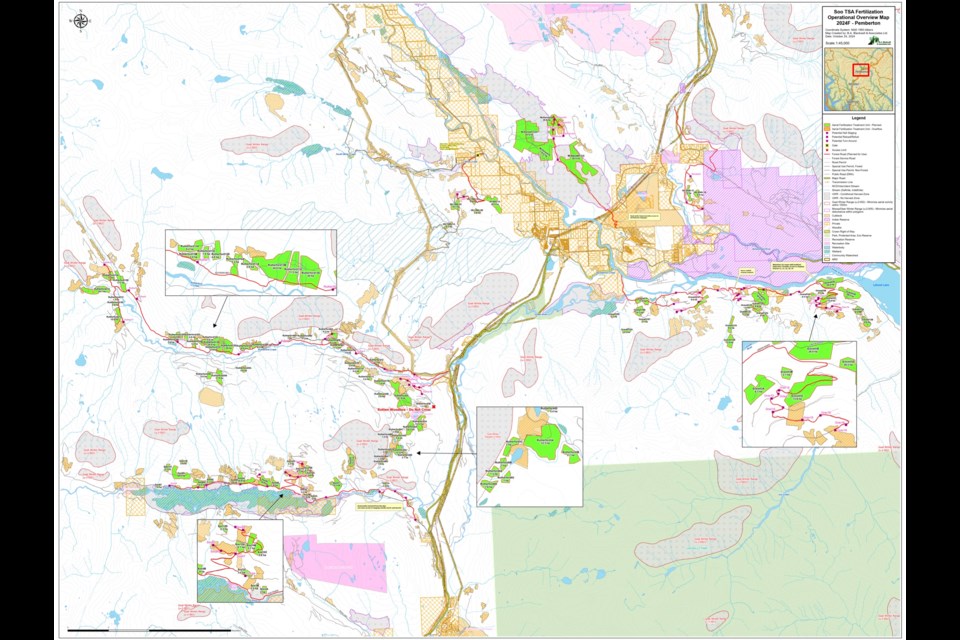

From now through November, helicopters will drop urea, a nitrogen fertilizer similar to what goes on lawns, on forests in Electoral Areas B, C and D near Lillooet, Pemberton and Squamish, and signage will be placed on roads to inform the public of safety hazards or delays, (SLRD). The plans have been approved by local First Nations, the Ministry of Forests and forest licensees.

The project is funded through the and administered by, a forestry consulting and environmental management company.

Jeff McWilliams, a senior associate with B.A. Blackwell, said programs like this have occurred in the Sea to Sky since the early 2000s. The program will start in the north and work its way south. McWilliams explained the program works by trucking fertilizer to designated areas for spreading, where it is loaded onto a helicopter that spreads it similarly to a lawn fertilizer.

“The helicopter has precise navigational direction," he said. "They've got the maps where the fertilizers will be applied, and they have to stay within those boundaries so that we make sure the fertilizer ends up where we planned it to go.”

Anyone recreating in these areas will see similar industrial activity to other industries. Radio communication, warnings at the bottom of roads and signage are posted, and drivers need to check for oncoming traffic.

For anyone hiking in the fertilized areas, McWilliams explained they aren’t at risk of injury.

“What they would experience are tiny bits of fertilizer that you would see put on your lawn in the spring, and that’s same material and that would fall," he said. "They're all small enough that they don't hurt anybody physically if they land on them; typically they land on the trees the branches above, and then they get knocked down through wind and rain to the ground.”

Significant health impacts would only occur if someone ingested a massive amount of the fertilizer.

Information published by the SLRD notes the benefits and objectives of fertilization:

- The first objective is sequestering carbon dioxide to mitigate climate change. Fertilizer improves nutrients for tree growth and subsequent atmospheric carbon storage.

- The second objective is “to improve timber volumes and value for future harvesting.”

- B.C.’s chief forester recommends fertilized stands grow for at least 7-10 years before harvest, but some harvest can happen in 5-7 years “with appropriate rationale.”

- Forest licensees are informed before fertilization, so it does not conflict with harvest plans.

- Increased forest volume “can be up to 30 cubic metres per hectare in a 10-year period.”

- Economic benefits of fertilization include employment and GDP, with “4.5 full-time equivalents (FTE) and $2.7M per 10,000 hectares of treatment, respectively.”

Forest fertilizer impacts

According to , forest fertilization has been used since 1981 in B.C. The application improves growth of Douglas-fir, western redcedar and spruce, but also impacts forest ecology.

Application avoids streams and bodies of water, and water-quality tests are performed to ensure run-off, if detected, is below maximum levels set by the Ministry of Environment for drinking water and aquatic life.

McWilliams noted streams, lakes and wetlands have buffer zones and are monitored, and adhere to MOE standards.

“If anybody's out drinking water from streams in the areas where we treat, they really shouldn't be worried that there's any significant health concerns,” he said.

Fertilization’s impact on “non-timber forest products,” otherwise known as “plants, wildlife and fungi,” shows Canadian undergrowth improved for certain herbs and shrubs, like Saskatoon berries, whereas dwarf shrubs like twinflower and dwarf blueberry declined from increasing competition.

Studies on the impact of mosses and lichens from forest fertilization show decline “in repeatedly fertilized stands,” though the pamphlet notes when forests are fertilized infrequently “these reductions in mosses and lichens are not as pronounced.” Woodland caribou can be affected through lack of food when lichens decline from fertilizing, which they rely on for foraging in winter.

Wildlife can be affected from direct exposure and shifts in plants growth which “favours some mammal species over others.”

Maps, fertilization standards and more .