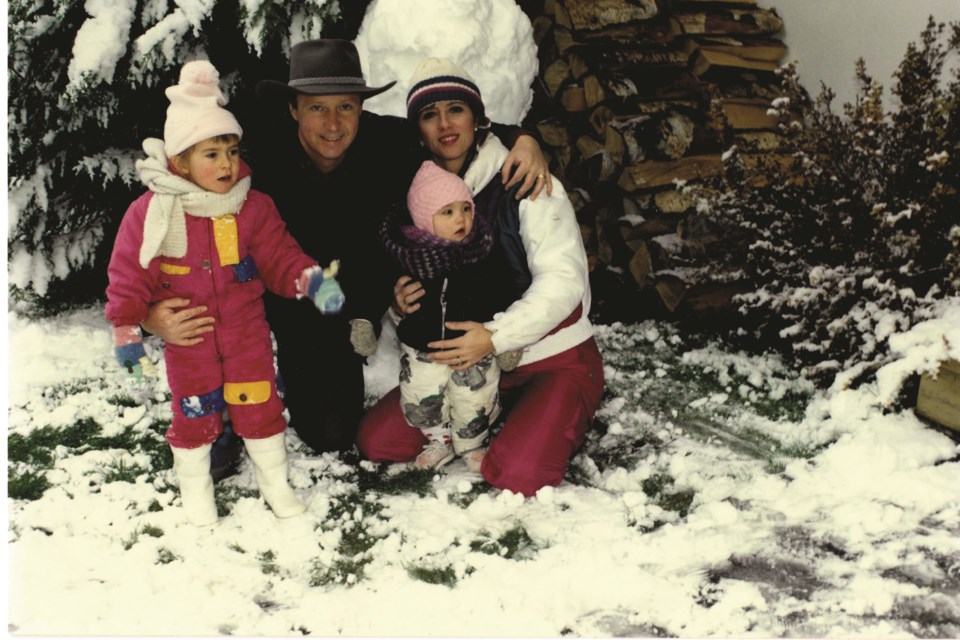

Whistler’s Rosemary Keevil had the picture-perfect life. A loving family. A doting husband and two adorable young daughters. A fast-paced career in media, hosting her own radio show.

Then, in the span of about a month in 1991, she was dealt two blows that would send her life into complete disarray: First, her husband was diagnosed with terminal lymphoma, followed by her brother’s AIDS diagnosis. In a little over a year, they would both be dead, at the age of 41.

“My life just went into a tailspin of emergencies and hospitals and needy kids,” Keevil says.

Suddenly thrust into single motherhood, Keevil says those first few years she was living off the adrenaline of raising two toddlers on her own. That is until one particularly debaucherous night when she dabbled in cocaine.

“I found it was the answer to all my problems,” she says. “It kickstarted a six-year spiral of drug and alcohol abuse.”

Keevil’s harrowing journey to the brink and back again is documented in her new memoir, The Art of Losing It, published by . A former and host of The Rosemary Keevil Show on Vancouver’s CFUN Radio, Keevil had to turn the lens on herself in this deeply personal memoir, an approach that took some getting used to for the career journalist.

“My editor and publisher, Brooke Warner, the founder of She Writes Press, when she read my first draft, she said, ‘Rosemary, your journalism is getting in the way. You’re stating the facts, and writing memoir is all about showing, not telling,’” she recalls. “Talking about myself came more into play during my time as a radio show host because it was sort of emotional radio and at one point we had to bare our soul a little bit—but I didn’t have much to bare at that point. I had to really get down to the fact that I had to talk about my own feelings and be prepared for the world to read that.”

Keevil describes herself during this period as a high-functioning alcoholic—although she considers the term a bit of a misnomer. She still made it to work on time, she still took her girls to and from school and appointments—“but I did many, many things that a parent shouldn’t do, like driving the kids drunk and stoned,” she says.

Keevil considers herself lucky she didn’t cause a fatal accident. The night she blacked out behind the wheel was her final wake-up call. “That was a gift,” she says, “a gift of desperation.”

In 2002, she checked herself into rehab, and hasn’t touched a drink or drug since. That would seem a natural place for Keevil’s story to finish, the shiny bow on an unimaginable struggle, but of course, recovery doesn’t end on the first day of sobriety—especially for a newly clean mom who had to essentially relearn how to parent her kids.

“You would expect that once I went in and got clean and sober that everything would be smooth-sailing. But it was a nightmare,” she says. “It was as if a wrench had been thrown into our family system.”

Accustomed to a mom who wasn’t always emotionally present in her drinking days, Keevil’s daughters bristled at all of the new rules and curfews she put in place once sober.

“They revolted,” she says. “My daughter once told me I was an effing bitch. She said, ‘I wish you never got sober.’”

Later, checked in to the family program at the Betty Ford Clinic, Keevil and her daughters learned how “one needs to go through a new brand of chaos” once sober, effectively rebuilding relationships from scratch again. “I had to learn how to parent my kids as a sober mother,” she adds.

Keevil joins a pantheon of memoirists who have written about their battles with grief and addiction, but where so many other self-help tomes offer quick fixes and cheap aphorisms to overcome their demons, The Art of Losing It drives home just how long and arduous the recovery journey really is.

Key to Keevil’s healing was allowing herself to fully grieve, to “fall apart,” along with accepting the things she had done in some of her darkest moments.

“The only way past it is through it,” says Keevil, before picking up her book to read aloud the last line: “I will also never lose the guilt I have over how I parented the girls in the absence of their dad, but I have acceptance. It’s what I’m doing about it now that matters today.”

The Art of Losing It is available in Whistler at Armchair Books and wherever books are sold. Learn more at .