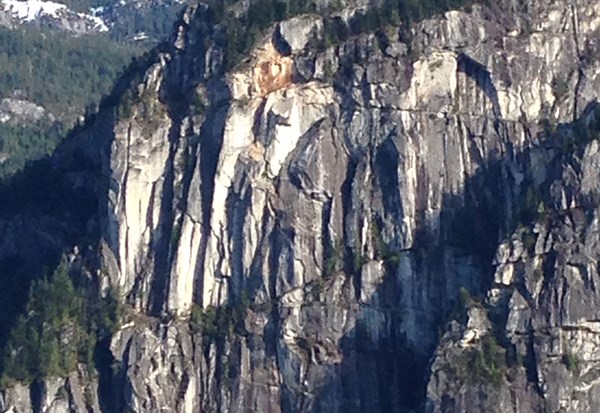

Late in the morning of Sunday, April 19, an enormous piece of the Stawamus Chief fell off and crashed into the forest below. A column of dust shot into the air and moved downwind through Valleycliffe.

Houses shook, windows rattled and then a deafening silence followed where there oddly seemed to be no highway noise, airplane noise or wind of any kind. After a few minutes, helicopters could be heard beating the air and sirens wailed.

Was this a rare and exciting event when you live in Squamish? Yes, but also amazing is how many of the long-time locals I’ve encountered talked of seeing and hearing rockfall from the Chief regularly throughout their lives. Many of these people aren’t climbers but share a long history of living in the shadow of the Chief.

I’ve lived here since 2002, and I can remember one other large rockfall event from a similar location, and I recall the strange hollow void it leaves in your stomach when you either witness or see the destruction left behind from an act of nature.

Moments after the event in April, I received a call from a friend who lives very close to the Chief’s North Walls in Valleycliffe. His voice had a far-away sound as he asked the whereabouts of several of our friends who might be climbing around that area. Calls went out, texts bounced and pinged, emails were dispatched; the search began for people climbing, hiking, bouldering in the area and for details about the event. Amazingly, no one was injured or killed, despite such a warm dry winter and spring ushering in an early start to the climbing season.

The North Walls of the Chief are a zone rife with moisture, greenery, moss, lichen and trees. The wall has a wild feel more akin to alpine climbing than roadside granite multipitch. A zone of more intensive freeze thaw cycles, it stays wet and cold because of its more northerly alignment. Moss fills cracks, bushes take hold, leaves collect and become dirt, and trees survive by burying roots deep in the exfoliating plates of stone which are forever feeling the pull of gravity, weathering, time and sloughing off from their ancient resting places. It’s no surprise that this was the area where the rockfall occurred, and its size is relative.

A friend has described the hourly occurrence of giant rockfall while climbing in the Waddington Mountain Range of B.C. and how this was what mountains do – fall down. Even the dry, seemingly bullet quality stone of Yosemite Valley in California sees huge rockfall right within one of the most popular national parks of the U.S. The mountains aren’t trying to kill; they are just slowly aging, like us.

Another view was that this event foreshadowed grim times ahead, relating back to the re-industrialization of our fjord with the liquefied natural gas (LNG) idea. An omen or sorts, it may be the harbinger of change. A friend with ties to the Stawamus First Nation said she had heard it was viewed as a bad omen by them, for the last event like this brought on the death of one of their respected chiefs. I heard tales of families trying desperately to move from the North Wall’s shadow because they felt confined and crushed beneath its looming presence. I also talked with a friend who, literally an hour after the dust settled, was off to hike into the fall out zone to see if new boulders had been deposited on the forest floor and could he be the first to find a new line. It’s safe to say that climbing The Northern Lights, a sought-after classic which lies beneath the rockfall’s path, is not going to happen right away this season. While the route looks like it escaped major destruction, its crux face climbing received a stone shave and a belay ledge further down the wall may have been taken out completely. Climbers on Angel’s Crest, a popular moderate multipitch opposite the devastation, had some serious luck that day as they watched part of the cliff fall past them and out of sight. Hopefully lottery tickets were purchased that evening?

As for myself, I have some strong memories of climbing The Northern Lights a few years ago with my partner, savouring each pitch as it became more and more wild as we approached the end of the route. We finished up the original finish, not the newer alternate Chilkoot Pass which was what fell off, and walked off in the dusk along an exposed trail near the edge of the North Wall. That trail, and everything beneath it, is now on the ground below.

The Chief is definitely aging and slowly falling down, so make sure you get up there and experience every inch of it that you can before it’s gone. What could possibly go wrong?