On Friday, Feb. 16, legendary Yosemite big wall pioneer and cutting-edge alpinist Jim Bridwell died in Palm Springs, California.

While always sad at the passing of someone woven so intimately into climbing’s cultural fabric, I wondered out loud if Jim’s passing wasn’t much much more than the complications of Hep C and the final dance in a lifetime of dangerous, committed climbing and adventuring as his son described in an online fundraising campaign to help cover expenses.

I wondered if Jim’s passing was a physical sign, an omen, of the changing nature of climbing in North America?

I might be extrapolating a bit; I might be theorizing on details that aren’t interconnected like I imagine they are, I might even be making a bit of a mountain out of the sad and final intimate pages of one man’s life. Whatever lines I might be reading between, it’s difficult to argue that Jim wasn’t one of the main forces in North America that shaped climbing’s attitudes and culture in the context of the ignorant world around us.

Who was Jim Bridwell and how did he shape North American climbing culture? Jim arrived in Yosemite in the early 60s as a quiet and observant 17 year old. Quickly and efficiently, he began tracking down and learning from a climbing lineage that started with Royal Robbins, Layton Kor, Chuck Pratt and Frank Sacherer.

Ethics and the game mattered; his teachers were the greats who birthed free climbing, clean protection, ground-up capsule style ascents and fair means, where you met the challenges the rock offered you with humility, low reliance upon gadgetry and the acceptance of risk.

These influences set the tone early and pushed him to begin amassing a long list of first ascents in Yosemite, most of which are now sought-after classics. Jim blended the ethics of Robbins and his contemporaries with the stone master’s love of hard free-climbing to act as an intermediary between climbing generations.

He was the first to usher in the division of the Yosemite Decimal System from 5.10 and 5.11 to 5.10 a, b, c and d.

Further, Jim knew that the challenges offered high up on the soaring burnished walls of Yosemite Valley were where the real beauty hung and would push the psychological barriers of climbers’ minds.

With the big walls looming skyward, Jim honed his aid craft until he began redefining what hard aid meant. Full pitches of hooking, beaks and other black arts skills meant that a fall on, for example, the Hook or Book pitch of Jim’s Sea of Dreams meant you either die or at best, get grievously mangled. He authored routes on El Cap such as the famous Sea of Dreams, the Pacific Ocean Wall, and Zenyatta Mondatta, all of which came with the most serious aid rating of A5. These routes all contain multiple pitches of barely body weight placements.

Finally came Jim’s third piece, his holy trinity of influence — the reliance on speed as a way of gaining a safety margin in the larger mountain ranges of the world. In a 2006 Alpinist magazine piece entitled “Bird’s Eye View,” Bridwell recalls:

“At 4 a.m. we started, without our headlamps, climbing by moonlight and memory—we’d already rehearsed the first four pitches and knew every move and every nut and pin placement by heart. With us, we had three nine-mil ropes of uncertain age and condition, twenty-five nuts, twenty-five pitons and one and a half gallons of water.”

Using Yosemite as his testing ground, on June 21st, 1975 he, Billy Westbay and Jon Long succeeded in climbing The Nose on El Capitan in under 24 hours, something on the scale of taming a gigantic and revered mythical creature armed with nothing other than some smooth talk, good pants and excellent jamming ability. Jim went on to make the first complete ascent of Patagonia’s Cerro Torre via the Compressor Route in 36 hours. Speed climbing tactics rounded out his quiver of skills, which included hard, committing aid climbing and cutting edge free climbing.

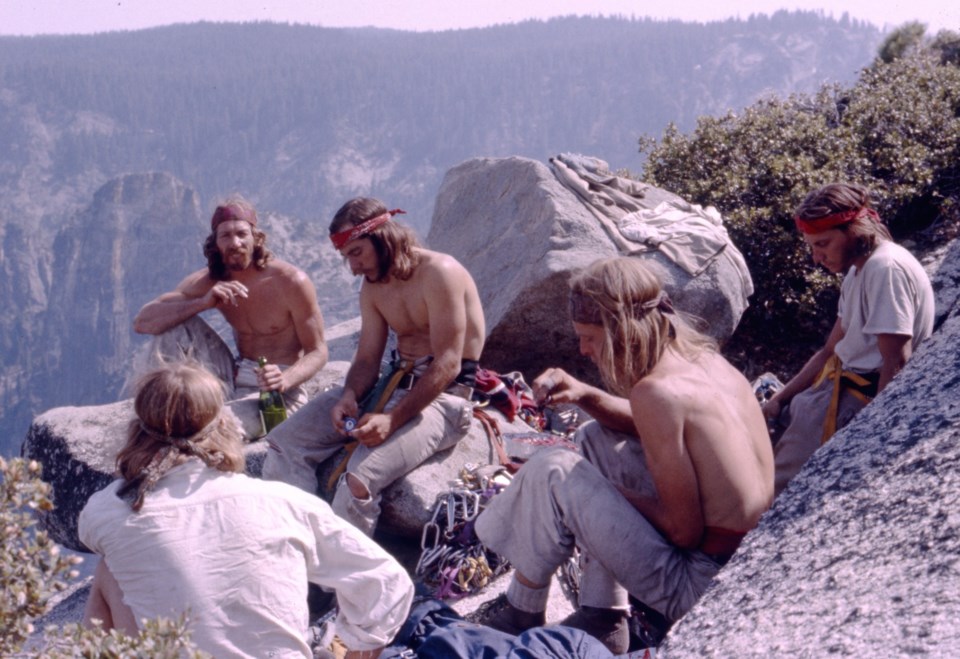

However, more than just the sum of the parts mentioned above, Jim Bridwell’s effect tied all this together with the irreverent, 60s counter culture attitude of utter self-reliance, psychedelia and blunt non-conformism. In a way, he represented a continuation in Warren Harding’s ideal that climbing existed as the arena where you alone had control, where no one could tell you what to do.

In Alpinist 18, Jim explained, “From my bird’s eye view at the top of the wall, anything now seemed possible. If I could imagine a route, I could climb it. Climbing had become a cause to live for—a way to prove the freedom of my mind.”

I can’t help but wonder if, as climbing slides slippery and self-congratulatingly alongside all the other Olympic sports, as climbing tips the scales towards absolute athleticism; towards ever increasing popularity and mass acceptance; towards major company sponsorship and social media film deals, towards grades hungry competitions won by younger and younger talents; towards crowded and garbage strewn crags, towards increasingly stretched thin volunteer rescue services, if we

haven’t lost something very precious and important with Jim’s passing.

Revering irreverence and thumbing our noses at the status quo, have we lost the peace that comes with climbing being a useless and ridiculous privilege?

A misunderstood act ignored by and looked down upon by daily life.