This week, 10 communities across coastal British Columbia will scramble to higher ground in an effort to flee an incoming tsunami. Fortunately, it’s just a practice run — all part of the seventh annual Tsunami Preparedness Week.

Known as the “,” the idea is to establish an escape route and practice reaching a tsunami safe zone to “build muscle memory,” as Mid-Island-Pacific Rim MLA Josie Osborne recently put it.

The event was traditionally held in preparation for a megathrust earthquake along the Cascadia subduction zone, which strike on average every 500 years.

But three months after a devastating volcano eruption in the island nation of Tonga prompted a tsunami advisory in B.C., it also begs the question: What else could trigger a tsunami in the province?

Perhaps more importantly, what can you do to prepare?

What warning will you get?

Your first warning will likely be shaking.

That's because a tsunami, or “harbour wave” in Japanese, is usually triggered by an underwater earthquake. A sudden shift in the ocean floor displaces the water column, sending a ripple of waves that gather in height as they approach the coast.

Such events are responsible for the devastating 2004 Boxing Day tsunami and earthquake that hit off the coast of Sumatra, Indonesia, killing over 230,000 people across multiple countries, as well as the up to 40-metre tsunami that rocked Japan in 2011.

The last megathrust earthquake to stir a tsunami toward B.C. was in the year 1700. Statistically, that means the next “Big One” has a 14 to 37 per cent chance of occurring over the next 50 years, according to some studies, though researchers warn it is just as likely to occur tomorrow or next century.

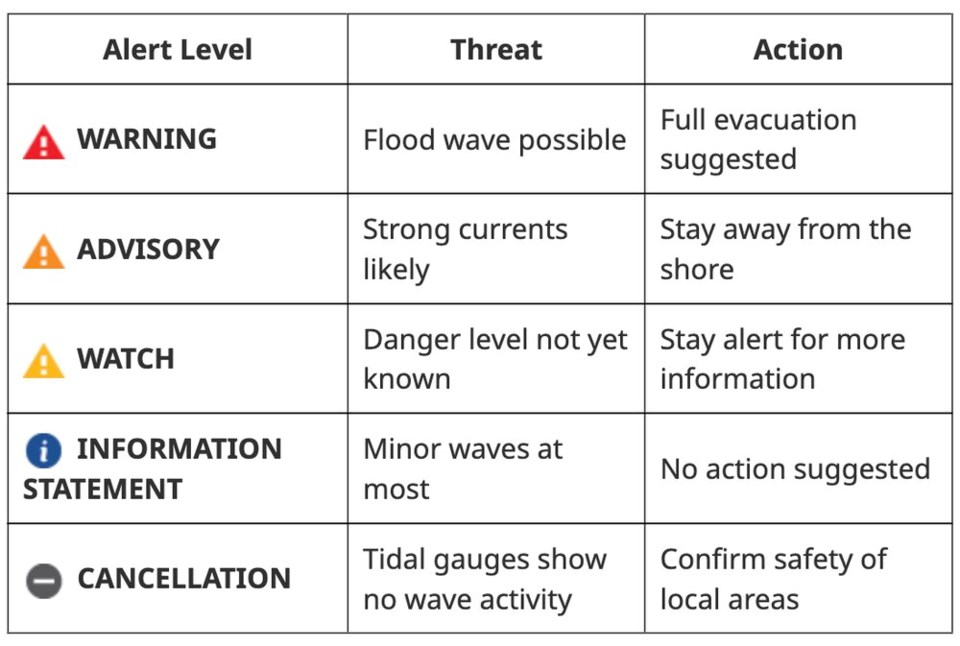

When a distant earthquake occurs, authorities might put out an information statement through radio, TV, text messages, telephone and social media. At this point, there's no need to panic.

If a watch is issued, a distant tsunami is possible, but it's not yet clear what danger is posed to B.C. communities. Coastal residents should pay close attention to further announcements and prepare to evacuate to at least 20 metres above sea level.

A tsunami advisory indicates strong currents and waves could be coming. People should stay away from shorelines and waterways where strong currents are likely. Pay attention to local government emergency alerts, coastal siren systems and the National Public Alerting System known as .

In the event of a megathrust earthquake, an up to 10-metre tsunami is expected to hit the West Coast communities of Vancouver Island — like Tofino, Port Alberni and Port Renfrew — within 10 to 20 minutes.

Unlike sea waves that gather strength from wind blowing over long distances, a tsunami’s long wave length strikes the coast as a surge of water, like a colossal tide that can’t be held back.

“It’s not one wave, it’s a series of waves that will last for hours,” says John Cassidy, a Victoria-based seismologist with the Geological Survey of Canada.

That kind of event would likely prompt a tsunami warning, indicating the worst may be on its way.

“If you’re near an inlet, ocean or lake and you feel shaking, move to higher ground,” said Cassidy.

And if higher ground isn't an option, head inland, recommends Emergency Management BC.

Planning before such an event can be crucial. The B.C. government recommends taking part in the annual (held virtually this year) and preparing an .

“You’ll be under a table holding on for four to five minutes. Then you have another five to 15 minutes to get to higher ground,” he said. “There’s not a lot of time.”

Will Vancouver Island protect the rest of B.C. from a tsunami?

The first up to 10-metre waves that hit Vancouver Island won't let up, warns Cassidy.

About an hour later, Victoria maximum wave heights are expected to crest to between four and 5.6 metres in the worst-case scenarios, according to a 2021 commissioned by the Capital Regional District.

“That’s a pretty big wave,” said John Clague, a geologist and seismic expert at Simon Fraser University. “A four-metre wave would flood the Inner Harbour and cause run-up to places like the Empress Hotel.”

As the tsunami waves bend around the southern end of Vancouver Island and into the Salish Sea, modelling says their height will decrease, dropping to between one and two metres by the time they reach Metro Vancouver.

Still, such a tsunami could cause widespread damage in Boundary Bay, where they're expected to be amplified, and devastate near-shore coastal infrastructure elsewhere.

“There’s going to be a lot of damage,” said Clague. “It rushes into these enclosed water bodies, it can overturn boats, dislodge wharfs.”

Tsunamis are not one-off events; as they roll in over hours, there's a high chance they could sync up with high tides, elevating water levels even higher.

Megathrust-triggered waves could also come from the north. In March 1964, a 9.2 magnitude earthquake struck off the coast of Alaska, with the resulting above-water and submarine landslides propagating a tsunami down into B.C.

As the second most powerful tsunami of the 20th century, the so-called Good Friday Earthquake and Tsunami produced wave heights up to 70 metres close to the quake’s epicentre.

By the time it reached Haida Gwaii, wave heights crested at over five metres. But it was in Port Alberni, roughly 1,500 kilometres away, where the province sustained the most damage, according to a 2018 re-imagining a similar event.

The town sits at the head of a long channel, so when the tsunami arrived, its power was amplified, once again climbing to over four metres as it closed in.

“It’s almost like a bathtub sloshing back and forth,” said Cassidy of the amplifying power inlet and fjords can have on tsunamis.

Displacement waves — a matter of when, not if

Earthquakes aren’t the only thing that cause tsunamis. Volcanic eruptions, meteor impacts, nuclear explosions and landslides — both undersea and from a hillside into a lake, fjord or ocean — can all trigger massive waves.

Smaller crustal quakes along active faults off the southern end of Vancouver Island or Puget Sound could also cause undersea landslides. One study found the underwater collapse of sediments off the Fraser River delta could theoretically send an .

Unlike a subduction quake and the “smoking gun, in your face” evidence of massive tsunamis off the coast of Vancouver Island, Clague says there’s little evidence the Salish Sea has seen large historic waves.

He’s also careful to note that geologic evidence for smaller waves in the one- to two-metre range expected during a subduction quake are nearly impossible to uncover.

A bigger concern, he says, are the undocumented slopes overhanging inlets, fjords and lakes across the province.

He points to 2007 when heavy rains dislodged a hillside overlooking , 80 kilometres east of Vancouver.

When it crashed into the water, it sent powerful waves hurtling toward the other end of the lake where they ran up nearly 40 metres, destroying an access road, forested area and several campsites.

“We kind of dodged a bullet on that,” said Clague. “If that had come down in July, it would have been well known to people because people would have died.”

How much risk B.C.’s coastal communities face from displacement tsunamis is not clear because there hasn’t been any , Clague and other experts tell Glacier Media.

That includes alpine areas, where researchers recently revealed just how lethal more intense rainfall and melting alpine ice can be.

In one destructive moment in November 2020, a mass of rock weighing the equivalent of all the automobiles in Canada slammed into the Elliot Lake, sending a more than 100-metre tsunami downriver and wiping out 8.5 kilometres of salmon habitat above Bute Inlet.

“The Chehalis Lake event was what I’d call a close call... We’ve seen what can happen at Elliot Creek,” said Clague. “Most of the lakes and coast in southern B.C. have people on the shorelines and some are bordered by steep rocks.”

“I’m actually surprised we haven’t had a disaster in the recent past.”