Imagine rolling down a highway on a hot day. Windows down, you suck in a breath — only instead of an exhilarating mix of coastal air, you choke down nearly six litres of diesel fumes.

Take a few more breaths and the pollution might irritate your eyes, nose, throat and lungs; drive or walk down that busy road every day and you up your chances of developing bronchitis, nausea and chronic headaches.

In the worst polluted areas of the world, such traffic-related air pollution is thought to kill roughly five million people every year.

“Over the long term, air pollution kills more people than any other environmental exposure,” said Dr. Chris Carlsten, a professor of respiratory medicine at the University of British Columbia.

Now, a new landmark study from two of B.C.’s leading universities has found diesel fumes could be even more insidious than once thought. While contributing to a long list of physical ailments, traffic pollution could also be undermining everything from people’s performance at work to their ability to daydream.

From correlation to causation

The genesis for the research began about six years ago, when Health Canada came to Carlsten with epidemiological data suggesting traffic pollution could influence people’s cognitive abilities. The problem, said the researcher and senior author on the Health Canada-funded study, is that nobody had directly measured the effects of pollution in a controlled setting.

“If you're not actually there, kind of having control over the scenario, you don't know what goes along with high pollution...” he said. “Is it actually the pollution or is it something else that tends to occur in the same scenarios?”

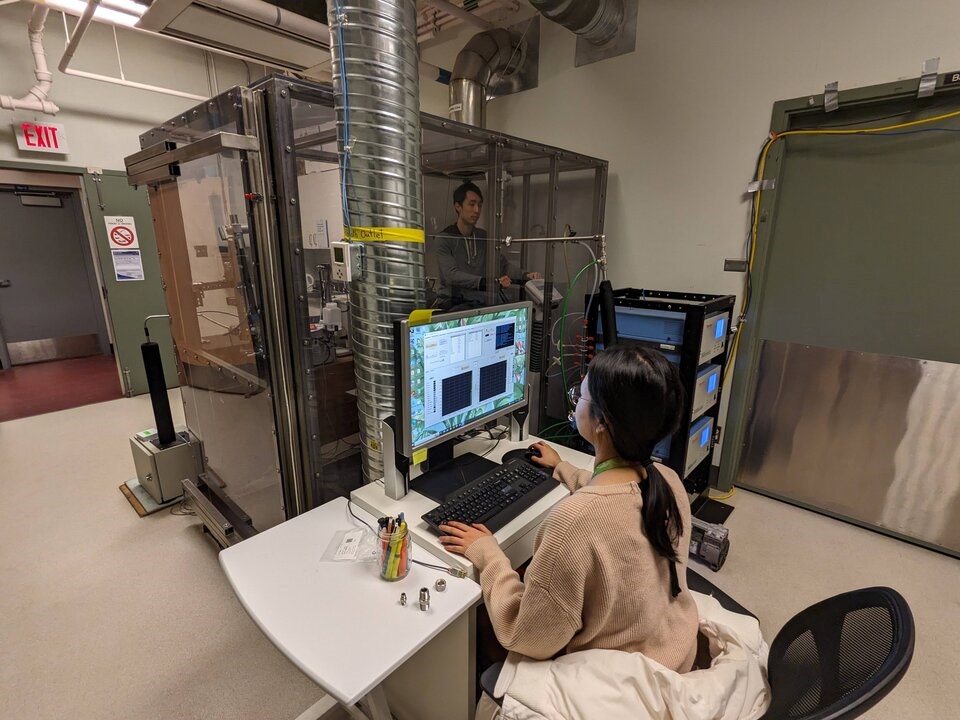

Carlsten's solution sits in a lab at Vancouver General Hospital. Built when the researcher first came to Vancouver in 2007, the UBC Air Pollution Exposure Laboratory contains an “exposure booth” that can mimic what it is like to breathe a variety of air pollutants. That includes diesel, a fuel that produces some of the most harmful ultra-fine particles.

In the past, Carlsten and his colleagues have investigated how traffic pollution aggravates asthma, mixes with allergens, and how diesel pollution filters through the lungs into the blood.

The lab’s latest study, published in the journal last week, marks the first time controlled human exposure has been combined with cutting-edge brain imaging technology.

The researchers recruited 25 healthy adults, and one at a time, sent them into the booth. For two hours, the participants surfed the internet or read a book while the researchers exposed them to both filtered air and diluted diesel exhaust comparable to air quality in Delhi, India — one of the most polluted cities in the world.

Before and after each exposure, the participants would spend about six minutes in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine, a non-invasive tool that can map brain activity in real time.

Dr. Jodie Gawryluk, who led the study as an associate professor in the University of Victoria’s Department of Psychology, said she was stunned when the results came back.

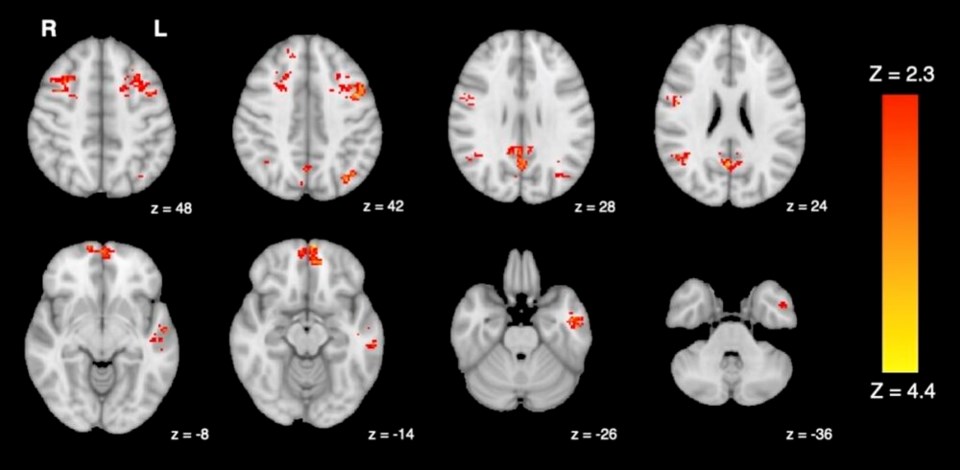

“You can see different places highlighted in red…” she said. “I was surprised.”

“It was quite widespread.”

Pollution appears to undermine memory, cognitive abilities

A specialist in brain imaging, Gawryluk usually investigates how aging affects cognitive decline.

That work often leads back to the default mode network (DMN), several interconnected parts of the brain that together play an important role in memory and internal thought.

“We tell them to lay still in the [fMRI] scanner for about six minutes and not think about anything in particular,” she said of the participants in the study. “Of course, you say that, and people start thinking about things.”

That internal reflection wouldn’t be possible without the default network taking over your brain. To call those moments “rest,” however, would be a mistake, and only shows “how far outside of consciousness” the default network operates, cognitive scientist Warren W. Tryon in a 2014 book.

First discovered in 2001, researchers have since found the DMN burns through more than 90 per cent of the energy consumed by the brain. The default network is active while asleep, and even continues to operate during light anesthesia.

When engaged, it triggers moments of introspective thought or reflection, autobiographical memories or imagined futures.

But disrupt the DMN and you potentially raise the risk of a number of brain disorders, such as autism, schizophrenia, or Alzheimer’s disease, have shown.

A call for vigilance

This isn't the first time a person's environment has been linked to those diseases. Recent studies tracking thousands of Metro Vancouver children over several years found living near traffic and further from green spaces and .

By exposing people to pollution in the lab, Gawryluk and Carlsten could filter out any other environmental factors that might influence its effects on the brain’s default network.

When Gawryluk first looked at the fMRI scans, she remembers seeing clusters of red dots lighting up several sections of the brain — each one a visual marker that pollution was suppressing the default network.

“We see traffic pollution leads to declines in cognitive function,” said Gawryluk. “It lets us draw really strong conclusions.”

While more work is needed, Gawryluk said she and her colleagues are already considering a ripple effect of consequences, including reduced cognitive performance in nearly every aspect of life, including at work.

After a short-term exposure, the participants' cognitive abilities recovered with a couple of hours. But long-term exposure — especially in where green spaces are less common — could matter for all sorts of diseases, say researchers.

“If you live in a city, or work in a job where there's frequent, ongoing repetitive diesel exhaust or other similar pollution exposure, then that could explain those long-term figures,” Carlsten said, pointing to the millions of traffic pollution deaths every year around the world.

While their study simulated exposures to air pollution in big Asian cities, Carlsten added that the rising frequency of wildfire smoke in B.C.’s large urban areas presents its own murky challenges. That will be the focus of the lab’s next study — to do the same thing with wildfire smoke as they did with traffic pollution.

“We need to keep pushing back on sources of air pollution because, unfortunately, we continue to face these scenarios,” he said.

Describing the results of their research “a call for vigilance,” Carlsten said the rising connection between air pollution and cognitive effects should prompt people to think twice about exposing themselves to traffic pollution.

Or as Gawryluk put it, “When we’re sitting in traffic and your windows are rolled down, you might think about rolling them up.”