Vancouver’s winter has seen a fundamental shift in recent years, as climate change pushes more winter days above freezing than in any other big city in Canada, a new analysis has found.

Between 2014 and 2023, the average number of winter days above zero degrees Celsius in Vancouver hit 69 a year — 19 days more than would have occurred without human-caused climate change, according to a global analysis from the U.S.-based research group Climate Central.

That’s more than the 13 non-freezing days climate change added to Toronto’s winter, and the six more above-freezing days now experienced in Montreal.

Kristina Dahl, vice-president for science at Climate Central, oversaw the science team that produced the research. Her team analyzed 10 years of temperature data captured around the world.

By comparing the world we live in with computer models showing a counterfactual world — one that would have been if climate change never happened — Dahl said they could calculate the number of winter days lost around the world due to climate change.

Dahl said she hopes the data will help people better understand what they are observing in their lives.

“Winter seems warmer than it used to be. We want them to make that connection that this is climate change,” she said. “You are seeing something real, and here’s exactly how real it is.”

B.C. Island communities lead spike in non-frozen days

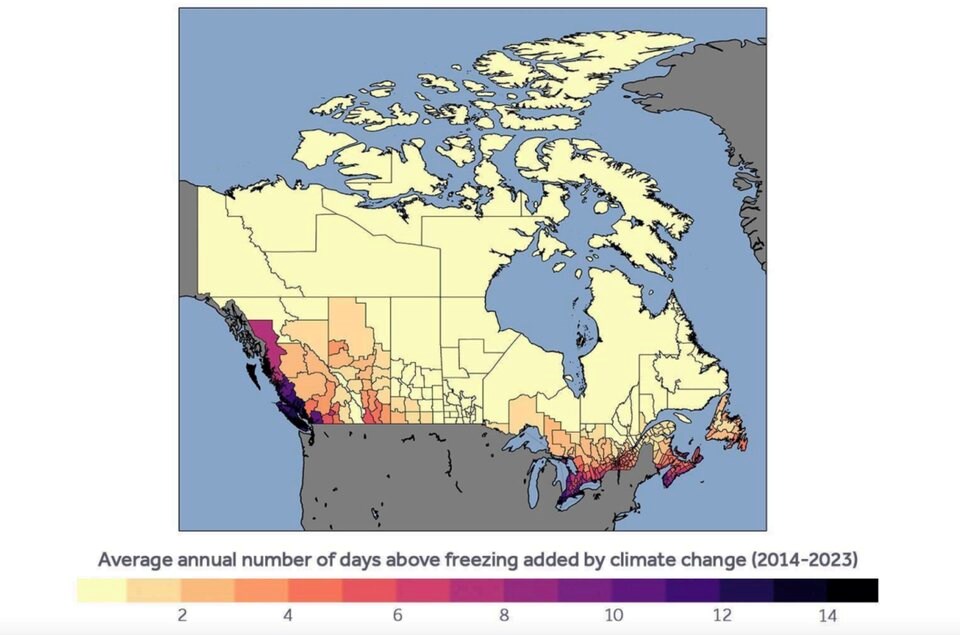

According to the analysis, five provinces — B.C., Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Ontario and Quebec — saw at least one more week worth of winter days above zero than would have happened in a world without climate change.

At a regional level, climate change drove three B.C. communities to see more above freezing days than any other region in Canada, according to Dahl’s team.

On Vancouver Island, Nanaimo and the Cowichan Valley led all other regions in the country with 18- and 17-day increases in above-zero temperatures. The wider Metro Vancouver region, meanwhile, saw its number of non-freezing winter days spike by 16 over the last decade.

Robert Whitewood, a climate scientist with a climatologist with Environment and Climate Change Canada who reviewed the data, said the results offer a window into how climate change is directly impacting Canadian population centres.

“It’s certainly not surprising,” he said. “We’re seeing more relative warming in the winter.”

The Climate Central data extended beyond Canada to every country in the world. Around 44 per cent of cities analyzed saw at least one additional week’s worth of days above freezing annually due to climate change.

The Japanese city of Fuji lost 35 freezing winter days, more than any other in the world. Some of the most heavily affected areas were in Europe, where cities in countries like Italy, Norway, Latvia and Denmark saw up to three more weeks of winter days above freezing.

Vancouver, with 19 winter days lost, ranks within the top 6.5 per cent of the world’s cities and puts it on par with the Polish city of Krakow, Rizhao in northeastern China, and Georgia’s capital Tbilisi.

Because the data presented by Climate Central uses zero degrees Celsius as a benchmark, Dahl said the analysis excludes warming trends seen in the colder parts of Canada — such as Canada’s North — which still rarely escape freezing winter conditions.

Whitewood said the global scope of the research was unprecedented and has repercussions for everything from tourism to pest control, as more insects survive winter temperatures and damage forests and crops.

“I’ve not seen something on this scale,” Whitewood said.

One reason the Climate Central scientists chose to look at lost winter days is because freezing temperatures have a strong influence on human activities and the natural world.

Many Indigenous communities rely on frozen conditions to hunt. In places like Western North America, Dahl said towns and cities depend on having a healthy snow pack that builds up over the winter and provides water during drier, hotter times of year. And certain winter sports and recreation simply require freezing conditions.

Philippe Marquis — a two-time Olympian who now coaches Canada’s national freestyle ski team — reviewed the Climate Central’s research just before it was published. He said it lined up with his own observations.

Growing up around Quebec City, Marquis said there was never any doubt wintertime snow was around the corner.

“The nicest memories I’ve got was just a white Christmas,” he said. “There was never at all a question about if we were going to ski around Christmas, if we’re going to be sliding and skating.”

But in recent years, he said that’s been replaced by a rising number of “brown Christmases” — snow accumulation a couple of weeks behind and lakes still not frozen over.

“The biggest thing is the uncertainty about everything,” he said. “We will get like crazy weeks where we’re deep down in the minus 10, minus 20s, and then we’ll get pouring rain.”

Marquis, who just returned from three weeks of training at Apex Mountain Ski Resort in the Okanagan, said he’s concerned about the longevity of the sport.

He pointed to Canada’s World Cup team, which was supposed to be in France last week until the trip got cancelled due to a lack of snow. Closer to home, Marquis sees the failure to open to ski training this summer as a small signal of something bigger.

“It doesn’t seem like much, but when you look down the history line and it’s never been the case, it has never happened, then you start questioning: What are we truly doing here to avoid those situation?” he said.

Marquis said he’s especially concerned for the coastal regions of B.C., where big populations are seeing an ever-narrowing window of cold winter temperatures.

The ski coach remembers attending ski events amid terrible conditions at Cypress Mountain Resort during the 2010 Vancouver Olympics. The latest data showing 19 fewer days of freezing temperatures in Vancouver has him worried those conditions are just a sign of things to come.

“I am very concerned when we look a little bit further in the next generation to come,” Marquis said. “We’ve built our economy, our culture around winter months. That’s what Canadians are.

“And to think that maybe our kids and grandkids might not really have access to the same climate and the same mountains that we have makes me extremely concerned — just for the pure joy and pure love of it all.”