That cute top you purchased for less than your morning coffee, wore twice, washed once, and threw away because it fell apart as soon as it hit the washing machine agitator will sit in a landfill, leeching pollutants for up to 200 years.

To put that in context, if fast fashion (and polyester) existed during Susan B. Anthony's lifetime, the dresses she would have worn advocating for women's rights would still be lingering in a Rochester landfill today. It is doubtful Anthony would have supported the murky ethics surrounding fast fashion, but that's beside the point.

In vogue, fast, and ultra-fast fashion—terms referring to the production speed—appeal to consumers because of their low price tags. To the individual, the financial burden is negligible. It may even feel like the responsible choice to buy from sites like Shein, Fashion Nova, or Zara. But in almost every other aspect, this type of clothing comes with a steep price to the planet. The fashion industry accounts for up to , according to the United Nations Environment Programme.

referenced news and fashion industry reports to break down the general life cycle of fast fashion. Before a polyester blouse is a blouse, it is a nonrenewable, petroleum-based synthetic that is . Garment workers around the world then manufacture it, often working in unsafe conditions and earning well below a living wage. After arriving at its destination via carbon-heavy international shipping, a blouse may serve its intended purpose for a year before spending the vast majority of its life as trash.

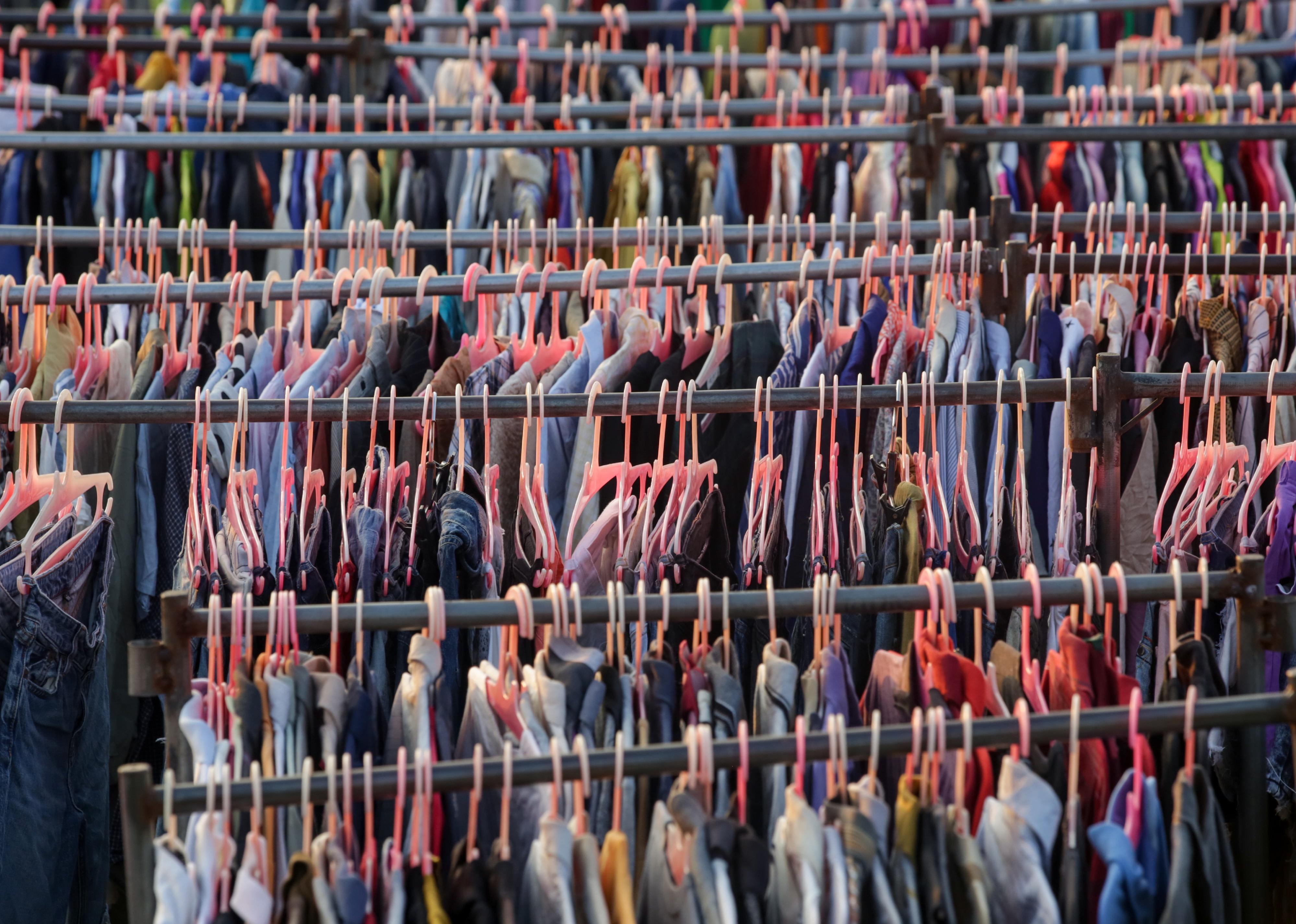

Primarily driven by consumers favoring quantity over quality and the rise of online shopping, the fashion industry is responsible for roughly the majority of which is either incinerated, dumped in landfills, or worse yet, polluting land, waterways, and coastlines around the world. Americans alone generate today as they did in 1960, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Some estimates put the amount of clothing produced yearly to be

The concept of recycling clothing, which many fast fashion companies have championed to help remedy the industry's wasteful reputation, is largely a myth. Only 1% of discarded garments are reused or recycled into new clothing. The technology and infrastructure necessary to process textile waste do not exist on a scale that can effectively keep up with the pace at which the world generates it.

Fast fashion companies turn tremendous profits despite low prices, low quality, and environmental detriment. Shein was valued at —more than Zara and H&M combined. Just two years ago, the online retailer was valued at $15 billion—a testament to consumer values that don't necessarily extend beyond their wallets.

triocean // Shutterstock

New designs daily, weekly

The fashion world follows a four-season calendar: spring/summer, pre-fall, autumn/winter, and resort. These seasons are traditionally heralded by high-end runway shows and . The world of fast and ultra-fast fashion lives not from season to season as dictated by the weather but from week to week or even day to day.

Companies like Fashion Nova can churn out more than , with a design going from concept to sample in just 24 hours. Shein, which is in a league all its own, adds roughly . This pace and volume lead to an enormous amount of overstock that eventually becomes harmful textile waste.

MikeDotta // Shutterstock

Material production

Polyester clothing, the most common material found on fast fashion sites, is manufactured from oil-based polyethylene terephthalate, a type of plastic. It is the worldwide.

Polyester production for the fashion industry accounts for one-fifth of the plastic produced globally and emits triple the amount of greenhouse gases of cotton production. Polyester is constantly shedding harmful pollutants called microplastics into the environment, primarily through wastewater.

Clothes from upscale and designer brands also often contain polyester, but the trouble comes from fast fashion's abundance and overproduction. Despite the harm, the polyester fiber market is expected to within the next decade.

JADE GAO/AFP via Getty Images

Product manufacturing

Roughly , but the fashion industry also has footholds in developing countries like Bangladesh and Cambodia, where labor is cheap and too often exploited. Estimates suggest more than 75 million people work in the garment industry worldwide.

A in Guangzhou, China, by a U.K. news crew revealed the extent of the company's . Workers must make upwards of 500 pieces daily for as little as 4 cents per garment. Companies even withhold wages if a worker makes a mistake. Shifts are 18 hours long, and workers may only receive one day off each month, violating China's labor laws.

Patrick Foto // Shutterstock

Worldwide shipping

Many fast fashion companies like Shein exist online only and rely on international shipping. Aviation and maritime shipping are massive sources of CO2 emissions. International shipping accounted for roughly in 2021—that 667 megatonnes of CO2 emitted.

Venn-Photo // Shutterstock

Consumer use

People are buying more clothes and wearing them less before throwing them away. In the U.S., the amount of textile waste equates to . Consumers wear most items —and in China, fewer than three times—on average before being discarded, partly because there are constantly new styles to update one's wardrobe with, and partly because the quality is so poor, it doesn't last.

Ernest Rose // Shutterstock

Disposal by landfill or incineration

According to a , the world sends the equivalent of one garbage truck full of textile waste to landfills and incinerators every second. Whether discarded clothing is burned or left to deteriorate in a landfill slowly, both outcomes release harmful greenhouse gases and petrochemicals into the environment. Polyester, in particular, can take between 20 and 200 years to degrade fully.

Fast fashion companies are not the only offenders of unethical practices. In 2018, high-end designer Burberry made headlines after it burned millions of dollars worth of unsold merchandise to prevent them from being sold cheaply, maintaining the brand's exclusivity.