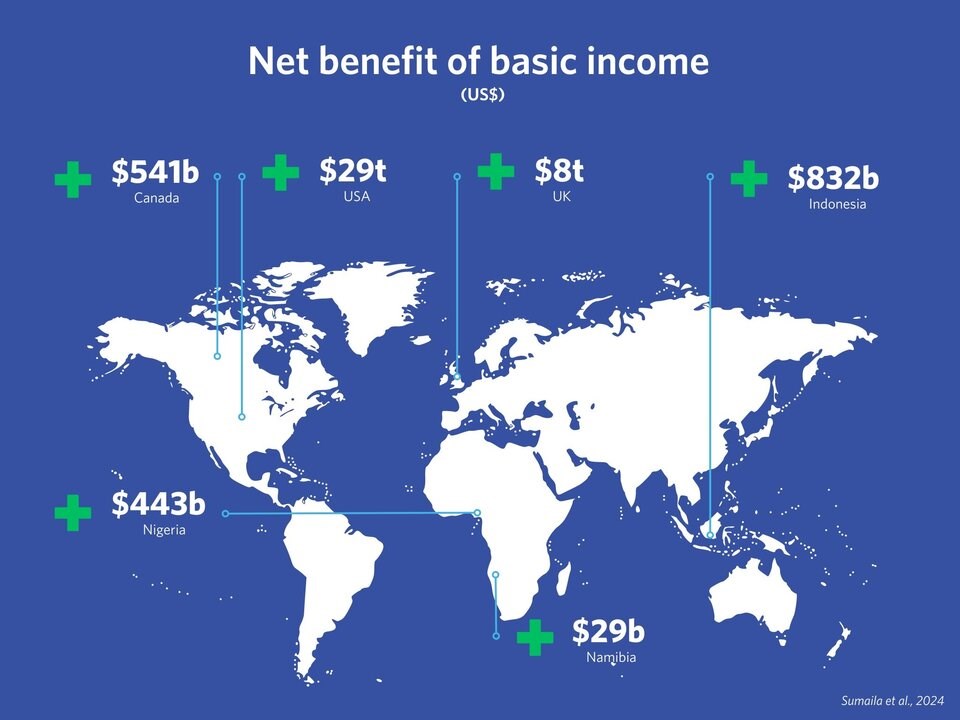

Providing a universal basic income to Canadians could help boost the country’s gross domestic product by $541 billion while giving its citizens a financial cushion against future climate catastrophes, a new study has found.

The , published Friday in the journal Cell Reports Sustainability, examined the impacts of a government-backed basic income across 186 countries.

It found that every dollar invested in basic income would generate between US$4 and US$7 of economic output. That could produce up to a $US163-trillion boost in global GDP.

If programs were funded under a “polluter pay” model, basic income could achieve a “double dividend” — alleviate poverty and environmental degradation, said lead author Rashid Sumaila, a trained economist and professor at the University of British Columbia’s Institute of Oceans and Fisheries and the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs.

“This kind of scheme will prepare the world — countries, communities — for the shocks that are almost sure to come with climate change,” said Sumaila. “It's huge.”

COVID-19 inspires global prospect of basic income

The idea of harnessing basic income to help solve several challenges facing humanity was borne out of the COVID-19 pandemic, Sumaila said.

“Suddenly we got hit by this shocker. People had to stay at home — no work, no income,” he said. “All these ad hoc things were put in place to try to keep us all going, people and the economy.”

In other words, COVID-19 showed us what can happen. If people have the basic income they need and are suddenly forced to shelter in their homes — whether due to a virus or a powerful storm — they will have enough to keep themselves alive, said the researcher.

In their study, Sumaila and more than a dozen colleagues spanning the United States, Sweden and Australia cite past research showing basic income is correlated with everything from improved sanitation, nutrition, and diminished hospitalizations to expanded educational access, reduced poverty-related crimes and substance abuse.

The study points to its “transformative potential” in places like Indonesia and Namibia, where basic income programs have led to substantial declines in deforestation and illegal hunting.

But debates over the provision of a basic income often hinge on two question: What will it cost? And who will pay for it?

“So we set out to say, how much will it cost the world to provide basic income to the whole population?” said Sumaila.

The study calculated the global cost to provide basic income to those below the poverty line at US$7.1 trillion. For the entire population, that number jumps to US$41.6 trillion, or roughly 30 per cent of current global GDP.

Stimulus from spending that money, however, would boost global GDP to between $49 trillion and $US163 trillion, the latter a four-fold return on the money spent, the authors found.

Experts divided on costs and benefits of basic income

How much individuals would receive in basic income would vary widely depending on the country’s population and wealth.

In India, past studies have suggested an annual basic income of between US$42 and US$217. In the , some have suggested individual basic income should distribute between £3,000 and £7,000. One group of researchers in the suggested annual basic incomes $10,000.

And in Canada, an provided $16,989 to $24,027 per year, adding $0.50 for every dollar made through employment earnings.

An looking at the program later found traditional social assistance programs presented participants with a number of bureaucratic hurdles while disincentivizing work. Those in the pilot, however, reported basic income had “improved their nutrition, health, housing stability, and social connections; and better facilitated long-term financial planning.”

A 2021 from Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Office later calculated a basic income of $17,000 would reduce poverty rates by more than 60 per cent in some parts of the country at a cost of $93 billion in 2025-2026.

But others have warned governments to avoid heading down the basic income path. In British Columbia, the provincial Green Party called for a study into basic income in 2018 as part of its confidence and supply agreement with the BC NDP.

In December 2020, a government-mandated panel released its findings in a 500-page . Its conclusion: basic income is too costly and causes economic distortions, including disincentives to work.

“A basic income is a very costly approach to addressing any specific goal, such as poverty reduction,” reads the panel’s final report.

Could basic income drive inflation?

Curiosity over the prospect of a basic income surged during the COVID-19 pandemic after many governments around the world rushed to send financial supports to its citizens.

“Might the pandemic pave the way for a universal basic income?” questioned one a year after the pandemic began.

“Pandemic proves it's time for basic income for all, economists say” read a two months later.

But as vaccines rolled out and the fear of infection faded, prices on a vast range of goods began to surge.

People around the world were faced with a whole new challenge as spiralling inflation raised the price of everything from groceries to fuel.

Many would later agree inflation was caused by a combination of a tight labour market, supply chain disruptions and rising consumer demand spurred by savings — including trillions of dollars in stimulus money handed out around the world.

Those conditions were compounded when in February 2022 Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine sparked further volatile price spikes in fuel and fertilizer, which in turn, filtered down to nearly everything for sale.

The UBC study claims a basic income program is unlikely to cause similar inflation, partly because many of the people who would receive the money live in poverty or countries that are experiencing widespread unemployment and would unlikely see an overheated economy.

'Inflationary pressures'

Sumaila and his colleagues acknowledge recent in Iran that found a 136 per cent rise in prices over five years after universal cash transfers were introduced in 2010. But in that case, the authors say the country’s political and economic situation makes it hard to blame inflation on basic income.

They caution the impact of basic income on inflation will depend on how people spend the money, current political and economic conditions, and how governments finance the program.

“One could argue that inflationary pressures could arise if the government decided to print money rather than pay for [basic income] costs through increased taxes or similar measures,” Sumaila and his co-authors write.

With that much money flowing through public coffers, any basic income program must also guard against individual misuse and systematic corruption, the authors warn.

Tax the polluters, suggest researchers

To pay for basic income programs — and avoid the rising carbon emissions and environmental degradation that could come with added consumption — the researchers calculate the prospect of a flat tax on the production of carbon emissions.

Taxing carbon from fossil fuel at $50 to $100 per tonne could raise US$2.3 trillion, a sum that would fund basic income for everyone living below the poverty line in Asia, Europe, and North America, the study found.

Sumaila said similar taxes could be applied to number of other industries that pollute or over-exploit natural resources — from plastic manufactures to fisheries, agriculture and forestry.

“Tax the CO2 emitters, those who empty the ocean, those who put plastic in the ocean,” said Sumaila. “That is going to raise quite a big chunk of the funding needed to do this.”

.jpg;w=960)

'Nitty gritty on the ground'

Sumaila pointed to already in place on Canadian industry as an example of how regulating greenhouse gas emissions could raise money for basic income.

In an industry like fisheries, he said paying a — the fishing of non-target species — could also offer a “very practical way” to prevent overfishing while helping to fund basic income.

Sumaila doesn’t claim his research group has all the answers on how basic income could be structured and funded across the world. He next plans to get groups together on each continent to sketch out a road map for interested governments.

“My hope is that we're going to get people around the world interested, to really do the nitty gritty on the ground on how to actually implement this,” he said.