“Good fortune” is the way Ron Ignace describes his early years. As a young boy, his great-grandfather would show him how to burn grass and shrubs to heal the land around Deadman’s Creek Valley.

“Then I got pulled off to residential school,” he said. “There's only one in this area — that's called Kamloops Indian Residential School.”

May 4, 1962, is still burned into Ignace’s memory: the day he ran away.

Ignace knew the school would come west to the Skeetchestn reserve to look for him. So, at 16 years old, he fled to an aunt’s house 80 kilometres to the north.

He went to work in saw mills and on railways, ranches and apple orchards.

“You name it,” he said, describing his tortuous path to Simon Fraser University, where he studied Indigenous oral history. He eventually made it back to Skeetchestn, where he would serve as chief for 32 years until his retirement last spring.

Thousands of other children, including one of Ignace’s aunts, never shared his fortune — their stories cut short, veiled in church records and in the memories of those who survived.

That is, until a rib bone surfaced in an old apple orchard. Next came a tooth. The Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Nation brought experts to uncover what time and earth had buried at the site of the old residential school.

On May 27, Kukpi7 (Chief) Rosanne Casimir told the world ground-penetrating radar had revealed the remains of 215 unmarked graves.

“I’m hoping that now that people will believe us when we say that there was a policy of genocide against Indigenous peoples,” Ignace told Glacier Media following the discovery.

From the 19th Century to the 1970s, more than 150,000 Indigenous children aged six to 16 were forced to attend state-funded Christian schools designed to assimilate them into Canadian society in what the has described as “cultural genocide.”

Children were removed from their families, not allowed to speak their own language and forced to convert to Christianity. More than 38,000 children were verbally, physically and sexually abused, triggering lifetimes of trauma. According to the TCR report, at least 6,000 Indigenous children are thought to have died between the 1880s and 1996.

As experts in Kamloops hunted down more than 200 “anomalies” on the 160-acre property, across Canada, other First Nations began to question whose lives were quietly snuffed out and buried on their own lands.

In late June, the Lower Kootenay Band said it had found 182 more unmarked graves at the former St. Eugene’s Mission School near Cranbrook; within two weeks, another 160 undocumented and unmarked graves were found near the . As of mid-December, searches at seven former residential schools in B.C., Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Nova Scotia have turned up nearly 1,400 suspected graves.

By some metrics, the grisly discoveries have finally spurred government to act. In July, the B.C. government said it would provide $475,000 to investigate each of the province’s 18 residential school sites and three hospitals; in August, Ottawa pledged another $321 million to help Indigenous communities search residential school rural sites.

But a true reckoning has just begun. First Nations across Canada are either actively searching or planning to dig up the past in at least another 16 schools.

What that means for reconciling Canada's atrocities against Indigenous peoples is not as clear. Seven months after the discovery in Kamloops, how far has the country really come?

B.C. FINDS HEALING IN GRIEF

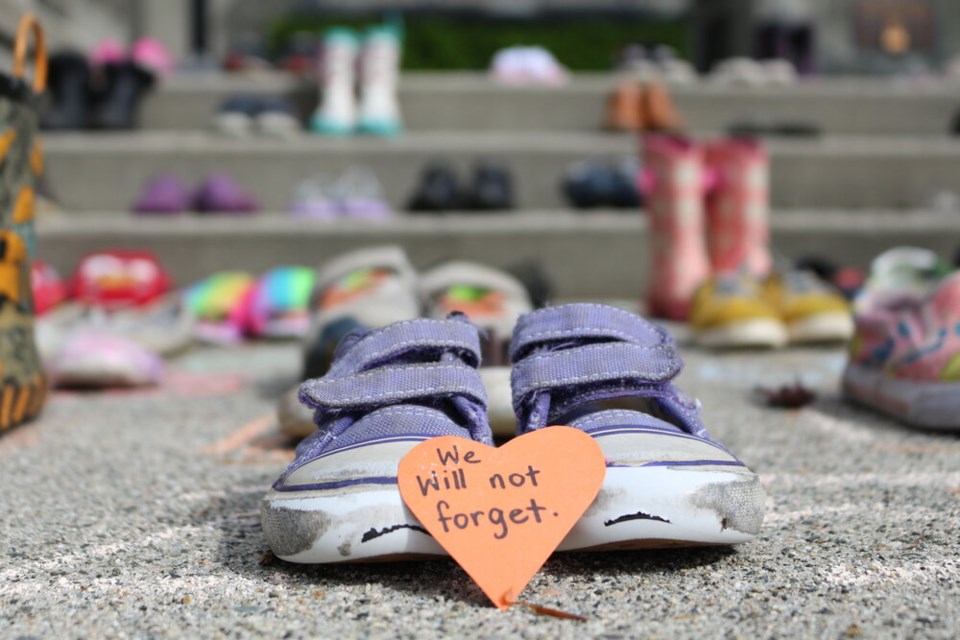

The graves in Kamloops instantly echoed in the lives of countless British Columbians, a void filled by public displays of emptiness.

215 vacant chairs on a school basketball court in North Vancouver.

215 cedar saplings planted in a .

215 pairs of shoes on the steps of an abandoned church outside Pemberton.

One Indigenous woman, herself a survivor of the , was left when a memorial sprung up on the steps of the Vancouver Art Gallery within 24 hours of the announcement.

Others took to the street. One Kamloops man committed to run 215 kilometres to help those who survived residential schools. In the end, tens of thousands of dollars would pour in.

“It is definitely a pivotal point in history,” said Casimir. “After years of silence and disbelief, our Kamloops Indian Residential School survivors, their firsthand knowledge about the deaths of children at the school feels like it's been finally confirmed.”

Canadians, she said, have all been awakened since the children were found, for the first time in Canadian history listening and understanding what residential school was all about.

“They want to know my story.

“They want to know what happened to my family.

“They’re looking at me differently.”

These are some remarks Casimir hears over and over as her community interacts with non-Indigenous people. Dark realities survivors had kept close for years started to reach the ears of non-Indigenous Canadians: residential schools were .

As Eldon Yellowhorn, SFU professor and principal investigator of a team identifying unmarked graves at Manitoba’s Brandon Indian Residential School put it: “It wasn’t secret that there were going to be deaths.”

RECONCILING IN CRISIS

In a year dominated by one crisis after another, a deadly heat dome and wildfire season quickly consumed the public conversation in B.C. But like so much public policy in Canada, it was and is Indigenous people that often bear the brunt of government failure.

Here's one example: the Canadian Wildland Fire Evacuation Database shows that roughly half of all wildfire evacuees in Canada over the past 40 years have been Indigenous, even though they make up less than five per cent of the country’s population.

In Ignace’s territory, it took the threatening his band’s survival before firefighters found a way to work alongside the First Nation. For two days, current Skeetchestn Indian Band Chief Darrel Draney said Emergency Management BC failed to return his calls for help.

“We had no response to anything,” Draney told Glacier Media as a “great wall of fire” approached his community in July. “No red shirts anywhere. No aircraft. Not even a visit.”

While most of the band evacuated, 75 people stayed behind. Soon after Draney spoke out to Glacier Media, BC Wildfire Service firefighters and Skeetchestn members found a way to come together. Skeetchestn hunters acted as experts on the ground, guiding firefighters to water sources and roads, and warning of wind changes.

As the chief said at the time, “Skeetchestn is the brains of this fire. The ministry is the brawn.”

Ignace, a traditional fire keeper for his people, continues to push for and educate how to carry out traditional burning, both to stimulate the land and to prevent wildfires. Heal the forests, grasslands and waterways of British Columbia, and you go a long way to healing a relationship with First Nations. Not to mention, preventing what Ignace foresees as “.”

The B.C. government has moved to improve forestry practices in the province, announcing in November it would defer old-growth logging in many areas to give it time to create a new industry paradigm.

As part of the process, on Nov. 4, the province gave First Nations 30 days to say whether they support deferrals, require further discussion or would rather work through existing treaties.

The Ministry of Forestry wouldn’t say how many First Nations have responded to the 30-day ultimatum. Grand Chief Stewart Phillip of the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs has slammed the time frame for such a complex analysis as “totally unreasonable.”

When asked where the B.C. government has made the most progress on reconciliation this year, a spokesperson for the B.C. Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation pointed to a number of bills. They range from amendments to statutes that confirm Indigenous peoples as full partners in sustainable forest management to bills that recognize Indigenous jurisdiction over education and child and family services.

The province predicts it will finalize an action plan in early spring 2022 to create a “whole-of-government road map over the next five years to advance reconciliation.”

“The residential school findings have increased the importance of reconciliation activities in B.C. and Canada and therefore increased public interest and government accountability in reconciling with First Nations,” wrote a spokesperson in an email.

Reconciliation demands such action, say all sides, but symbols of support and the words that come with them matter too.

A SERIES OF MISSTEPS

Governor General Mary Simon was sworn into her position in July as the first Indigenous representative of the Queen Elizabeth II in Canada. When she delivered her throne speech in Inuktitut, she was the first to do so in an Indigenous language, kicking off Parliament this fall with reminders of the “deep wounds” opened by the discovery of the Kamloops grave sites.

This was a year when Canada stayed home to commemorate the country’s first ever National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. On a day meant for reflection, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau ignored invitations to visit the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Nation in Kamloops, instead opting to quietly vacation in Tofino, B.C.

Two weeks later, when the prime minister finally visited the First Nation, Chief Casimir slammed Trudeau for squandering a chance to heal.

“The shock, anger and sorrow and disbelief was palpable in our community. And it rippled throughout the world to say the least,” said Casimir as Trudeau sat beside her.

Today, Casimir said it was never too late for the prime minister to make things right. When he did eventually show up, spending the whole day with the nation's leadership and residential school survivors went a long way to carrying on a mandate toward reconciliation.

Casimir also pointed to the importance of establishing a healing centre, museum and Elder's lodge over the next five to 10 years — three things the Canadian government has acknowledged with “meaningful gestures” but that still lack action, according to Casimir.

Within weeks of Trudeau's visit, political missteps were once again braided into disaster. When November’s floods ravaged the southern half of the province, several First Nations communities were cut off from the world as their territories slipped into the river along Highway 8.

Again, those First Nations were left off Trudeau’s itinerary when he came to visit a province in another state of emergency. Shackan Indian Band Chief Arnold Lampreau said a lot of his community spent nights sleeping in cars waiting for a call from Emergency Management BC.

“The prime minister has gone to Abbotsford. He flew right over top of me and I’m pissed off,” said Lampreau, speaking to Glacier Media after evacuating to Merritt.

“He should have stopped off. If he doesn’t want to come here, I’m going to go pound on his door.”

CHURCH APOLOGY, STUDENT RECORDS A PRIORITY

Where politicians have floundered some have expressed hope the church could offer some closure.

Casimir said her nation is looking at pursuing criminal investigations related the findings at the Kamloops Indian Residential School. But a more urgent priority is ensuring student records held by the Roman Catholic Church and federal government are released to survivors.

Federal Minister of Justice David Lametti assured Casimir student records from the school — now in Ottawa's hands — will be released to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission within the next 30 days or so, according to the chief.

With “complete and full disclosure,” Casimir said those school documents must be made accessible to survivors. But they are also crucial sources of information to identify buried children, the circumstances that led to their deaths and to help repatriate their bodies to their home communities — thought to stretch across B.C., and as far away as Washington State, Alberta and Yukon.

“How do we heal?” said Casimir. “We're still all grappling with the truth.”

The discovery of the graves has already pushed the Catholic community to levels of contrition never seen before. A week before National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops issued a to residential school survivors, acknowledging “grave abuses” committed by “some members of our Catholic community.”

Three days later, the said it would commit $30 million over five years to advance reconciliation at the local level across Canada.

“We hope and want that to be meaningful,” said Casimir, with a caveat. “There’s never been an apology from the highest level of the Roman Catholic Church.”

That could soon change. Pope Francis is scheduled to host an Indigenous delegation ; he's also expected to make a trip to Canada in the new year, a pilgrimage that would answer the .

“We at the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc want to be that host community that he visits,” said Casimir. “We do want to see the Holy See issue an apology.”

MEASURING NATIONAL PROGRESS ON RECONCILIATION

At a national level, progress on the Truth and Reconciliation’s 94 calls to action has seen mixed results.

According to the , which seeks to track progress on the TRC’s recommendations, only 13 have been completed. Another 29 calls to action have been met with “projects underway,” while 32 have had “projects proposed” and 20 have “not started.”

There has been some progress in 2021.

Roughly two weeks after the graves in Kamloops were discovered, Ignace was appointed the first . A position independent from the Government of Canada, the posting answers the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 14th call to action.

“Our languages will no longer stand in the shadow of other languages here in our land,” he's .

But advancing Ignace into his new position is one of few bright spots on reconciliation's national stage.

Eva Jewell, research director of the First Nations-led think tank the , said counting proposed projects gives “a false sense of advancement” on reconciliation.

In a report released Dec. 15 tracking progress on the TCR recommendations throughout 2021, Jewell and co-author Ian Mosby found only 11 of the 94 calls to action have been completed to date. Of those, three of the recommendations — appointing Ignace as language commissioner, establishing a National Day for Truth and Reconciliation and replacing the Oath of Citizenship to acknowledge “the laws of Canada including Treaties with Indigenous Peoples” — were advanced this year.

In a period of three weeks, all in the month of June and all after the 215 graves were found, more was accomplished on the TRC's calls to action than in the previous three years, according to the report.

Two days before the report was released, the Government of Canada said it would provide $40 billion in compensation to Indigenous children wrongfully caught up in an underfunded child welfare system and to “implement long-term reform so that future generations of First Nations children will never face the same systemic tragedies.”

“Historic injustices require historic reparations,” read a statement from Indigenous Services Canada Monday.

As the latest chapter in systematic discrimination against Indigenous children, it’s not clear when or how the money will be paid, or if ongoing litigation will be dropped as a result. Further details, said Ottawa, would be made public on the last day of 2021.

The federal Ministry of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs did not respond to Glacier Media's request to account for its progress on reconciliation since the discovery of the unmarked graves in Kamloops.

But zooming out on the past year, and using what the Jewell and Mosby describe as the CBC's “most generous measure on calls to action,” Canada moves into 2022 with an “abysmal” 14 per cent completion rate on the TCR's calls to action. Under their own metrics, that completion rate falls to under 12 per cent, a pace of progress so slow Jewell and Mosby question whether they will continue their work into the new year.

“Canada has demonstrated time and again — in its intent, policy, and political culture — that Indigenous peoples are a project to complete or a 'problem' to be solved,” wrote the researchers.

“To the question, 'When will it be enough?' we say: it will be enough when the systems of oppression no longer exist.”

The Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line (1-866-925-4419) is available 24 hours a day for anyone experiencing pain or distress as a result of their residential school experience.