The sheep have been sheared and the lambs are starting to drop at Parry Bay Sheep Farm in Metchosin.

Lamb prices have never been better, but John and Lorraine Buchanan are at a loss when it comes to the endless amounts of wool that comes off their ewes and market lambs.

The Island’s largest sheep farmers, with about 300 ewes, are sitting on mountains of wool — but the market price for sheep fibre has hit the floor.

Wool is fetching 10 to 70 cents a pound today, depending on the type and quality, down from $2 to $5 a decade ago, and much more historically. Since 2018, the price of wool on the world market has slid more than 65%.

John Buchanan said those prices don’t come close to covering the costs of shearing or even the heavy burlap bags needed for shipping, not to mention the labour associated with picking out the poop and packing the wool — and certainly not the transportation costs over to the Lower Mainland to deliver it to depots and eventually mills in Alberta and Ontario.

“In the old days, a fleece was worth a day’s work … now it’s less than five minutes,” says John, who has been farming sheep since 1969 on the Island. “The farmer I learned from said he would pay for his winter feed from the wool he took off that year, and the lambs were going to be for his wages. Now winter feed is nearly $200 [a sheep] and the wool isn’t even worth a dollar.”

Shearers, who take five to eight pounds of wool off each sheep, charge up to $15 per animal.

“It’s just not worth selling it anymore for the amount of work you’ve got to do to sell it,” said Lorraine Buchanan.

The collapsing market for Canadian wool is being blamed on several factors, including a shift to producing polyester and plastic-fibre textiles.

China — the largest buyer of Canadian wool — also placed embargoes on wool and other goods after the arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou in late 2018. The start of the pandemic in 2019 and the shutdown of factories and mills led to a global oversupply that put wool prices in free fall.

The Buchanans have burned wool in some years, and at times thrown it into the compost to augment hay fields or grain crops. And they say a lot of smaller producers have done the same.

“Most of the wool that’s grown around here gets thrown away,” said John. “If you’ve got five sheep and you’re getting a dollar a fleece, it’s not worth worrying about.”

Compounding the problem is the fact there are no local wool mills left to process the fleeces. Like dominoes, Island mills have disappeared over the years, with facilities in Qualicum Bay, Duncan, Metchosin, Saanich and Salt Spring Island all shutting down.

What remains on the Island are small-scale wool processors, largely individual weavers and artisans.

In B.C., there is just one major wool mill left, located in Kamloops.

The Buchanans are storing about 4,500 pounds of wool from their own and other farmers’ animals. It’s packed in tight burlap sacks sitting between stacks of hay bales in a former chicken barn about a kilometre from their home farm.

They are counting on the Canadian Co-operative Wool Growers — a national group that markets nearly all the wool produced by Canada’s 9,400 sheep farmers — to arrange for an Island pickup in September.

The wool is shipped from depots in the Fraser Valley and Kamloops and trucked to mills in Lethbridge or Carstairs, Alta., or loaded onto trains to Carleton Place, Ont., where it’s graded and prepared for world markets.

“The wool co-op still wants it, but the question is how much are they going to pay us?” said John Buchanan.

The co-op has done pickups the last two years and it’s the only way that makes it viable for the Buchanans.

“Otherwise I have to make a couple of ferry trips with truck and trailer, there’s the gas and the wages I have to pay for someone else to be doing the work I’m doing [on the farm],” he said.

Barbara Ydenberg, B.C. director for the Canadian Co-operative Wool Growers, who operates a 60-head sheep farm in Langley, said it’s a challenge for Island producers who face the extra cost of ferries to bring their wool to a depot.

“Island farmers aren’t getting the price for wool that makes it worthwhile for them,” she said.

Instead of keeping it clean and dry, many aren’t bothering to even keep it. “Wool Growers is trying to make an effort to collect it, but there isn’t enough wool to collect, so it’s a vicious circle, really.”

Ydenberg said she will be brainstorming with Island farmers about getting a depot and regular pickup service for wool. She said one solution may be semi trucks that deliver hay to the Island or other vehicles that bring loads and come back empty.

Christine Stephens, owner of Walnut Hill Sheep Farm in Abbotsford, sets up a depot for the Canadian Co-operative Wool Growers every year — one of about five in the province where farmers can drop off their fleece for shipment.

But the collections have declined steeply as wool prices plummet.

In 2012, Stephens collected 20,954 pounds from more than 100 farmers. Last year, just under 2,200 pounds of wool from 11 producers was dropped off.

The Canadian Co-operative Wool Growers pays for all the shipping eastward, but Stevens said it’s still not worthwhile for many farmers because of shearing and labour costs and the fuel needed to deliver fleeces to depots.

“I have farmers who live in Maple Ridge fairly close to me and they say it’s not worth the fuel to deliver them,” said Stevens. “So you can imagine the farmers on the Island, or even places like Williams Lake. The depots are few and far between for them to get their wool to market.”

The oversupply crisis

The Canadian Co-operative Wool Growers, with its central clearing house in Carleton Place, Ont., southwest of Ottawa, grades and markets about three million pounds of raw wool a year, the majority from Quebec, Ontario and Alberta.

The fine, medium and coarse wools are manually graded according to fibre diameter and length, amount of grease and foreign matter and the quality and method of preparation, and sold wherever the best price is available.

Its main buyers have been from China, Egypt, India and South America. It’s trying to sell in other countries, but Canada produces just a sliver of the 400 million tonnes of wool produced a year worldwide.

And while demand for fine wool such as Merino — from Merino sheep — is up, coarser types produced in Canada have tanked by more than 65% since 2018.

While its warehouse and grading facility are packed, the co-op is still taking fibre and asking farmers to continue to store their fleece for when the markets improve.

In the meantime, Leanna Maksymiuk has a solution to all the wool that’s being tossed into compost piles, burned or dumped in landfills.

She makes fertilizer pellets from wool on her family’s small sheep farm in Lumby, east of Vernon.

It’s not a new thing. Wool pellets have been manufactured in Europe for decades, and Maksymiuk believes the timing is right for new markets for B.C. wool.

“There’s no shortage of wool and people are throwing it away when it’s a very beneficial product for the soil,” said Maksymiuk, who started Waste Not Wool Pellets last June. She and her husband, Mark, acquired a pelleting machine from a manufacturer in the Czech Republic and can produce about 125 pounds of pellets an hour.

She’s already collected more than 6,000 pounds of fleece and waste wool and is processing the material, selling online and in a growing number of retailers. She’s eager to expand outside the Okanagan.

The pellets provide nutrients and organic material as they break down — they contain manure and organic vegetable matter such as straw and carbon, which sheep naturally sequester in their wool.

They also help gardens retain moisture, as wool holds up to 30% of its weight in water.

Some garden experts also say the wool pellets are a natural slug deterrent, since they contain tiny barbs — the same ones that make wool itch.

The raw wool is shredded into a consistent length and texture before it’s sent into the mill, which releases high pressure valves to push the wool through and extrude pellets.

The pellets sell in half-kilogram to two-kilogram bags ranging from $17 to $42, with larger quantities available.

Maksymiuk said the business not only helps the struggling B.C. wool industry, it boosts food and plant production in times of severe drought.

“So instead of burning it, which you really can’t do in the Okanagan anymore because of the fire bans, or taking it to a landfill, we want to come and get it,” said Maksymiuk. “We’ve seen farmers who have 10 years worth of wool and really don’t know what to do with it.”

As the business grows, Maksymiuk is considering developing depots for waste wool, including on the Island.

According to the Woolmark Company, which certifies products and fashions for the industry, wool biodegrades in as little as three to four months, releasing nitrogen, sulphur and carbon into the soil as a slow-release fertilizer.

Ydenberg said the Canadian Co-operative Wool Growers is also studying new uses for wool, including as packaging fill that can replace polystyrene foam, and as home insulation.

A study by Halifax’s Dalhousie University found sheep’s wool as insulation — while effective — would be a hard sell on an industrial scale. Wool is naturally fire retardant — though it does melt — and has good thermal capabilities in line with fibreglass insulation. It is used in Europe and other parts of the world and in smaller homes like log cabins.

But it would be hard for Canada to meet demand on a large scale, especially given the time and costs to clean and prepare the wool, according to the Dalhousie study. There might also be insurance questions because wool isn’t officially recognized by insurance companies or builders as an insulation product.

The vanishing wool mills

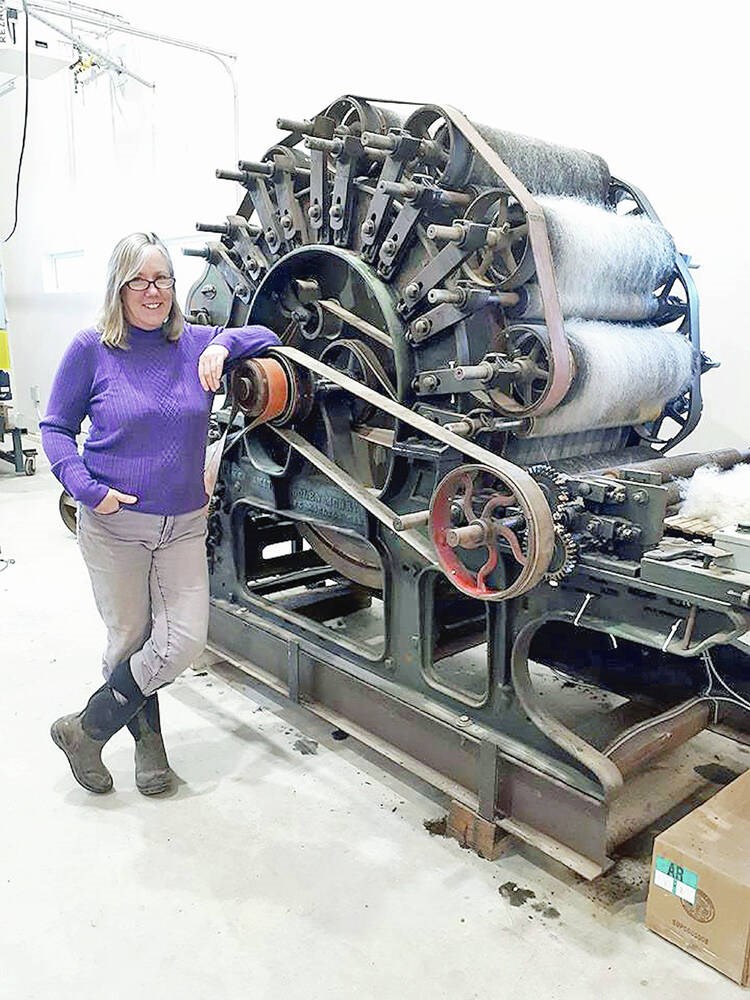

Tracy Brennan operated the last big wool mill on Vancouver Island, operating from early 2018 to April 2020.

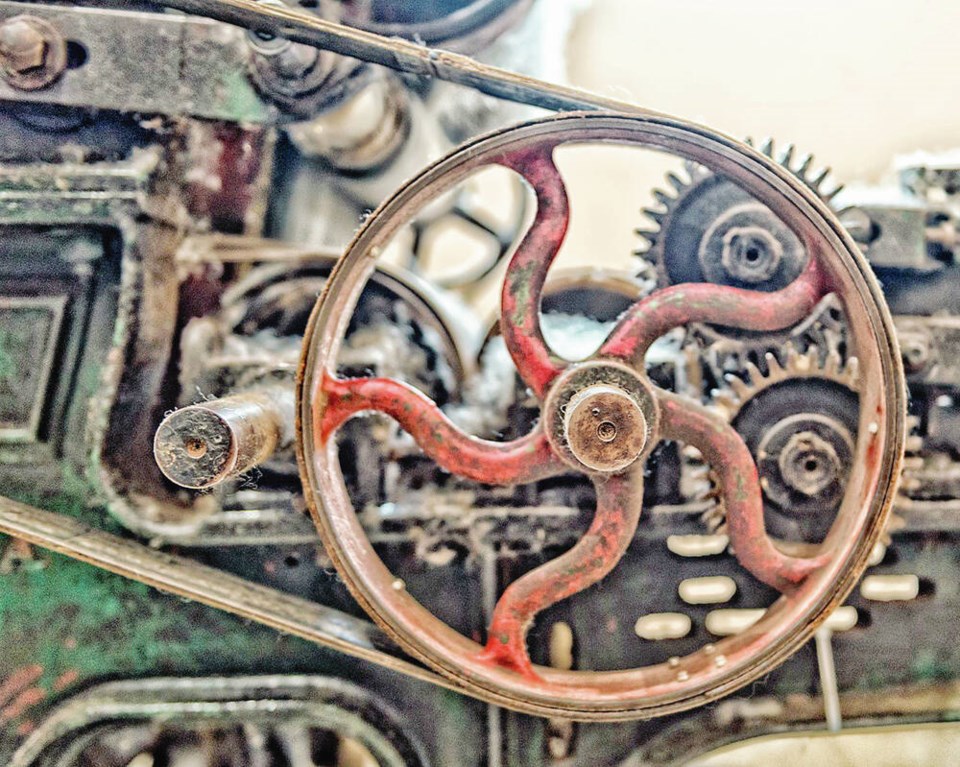

She had pieced together a patchwork of equipment — including an 1870-built carding machine made in Philadelphia that was the longest continually operated machine of its kind in North America — and produced custom yarns and wool batts for three years.

Farmers would bring in their fleeces from specific sheep or alpaca, providing traceable products from animals raised locally, with premium resale prices.

Brennan said the Inca Dinca Do mill in Central Saanich had just hit its stride, catching up on demand from farmers and artisans as six employees washed, scoured, carded and spun wool, alpaca and llama fibre into yarns.

Then COVID-19 and personal challenges abruptly changed her plans.

Her father’s health declined and a decision was made to sell the farm where the mill operated in North Saanich.

“The first couple of years were a learning curve,” said Brennan. “Just before COVID and the decision to sell the farm, we are on a track to make money. We were really making it work. I guess if I did it again, I would do it with new equipment. It has to be efficient to stay afloat.”

In the Cowichan Valley, there was a carding mill from 1978 until about a decade ago, when Sarah Modeste, a Cowichan Tribes member, closed it down. The Modeste carding machine now sits in a Crofton warehouse.

Theresa Smith, who has been knitting the famed Cowichan sweaters for more than 40 years — since she was 12 — said many Cowichan knitters now source their Canadian yarns from distributors on the Lower Mainland and Alberta.

Some of the wool used to come directly from the Buchanans’ sheep farm in Metchosin, but since the local mill closed, yarns are sourced elsewhere.

Turning raw wool or fibre into yarn is a labour-intensive and time-consuming process. There are multiple stages involving washing and scouring the wool, carding the fibre, combing and refining, spinning the fibre into continuous threads and then skeining, or winding, the yarn.

Nicole and Jeff Link now operate the province’s only full-service fibre mill out of a 6,000-square-foot facility in Kamloops.

That Darn Yarn Shop and Fibre Mill has been operating for six years, producing high-quality yarn from wool, alpaca and bison fibres — even musk ox. But their wait list is long for new clients — up to 18 months, said Nicole Link.

“We work really hard and don’t pay ourselves very much,” she said. “There’s a lot to the process. It’s time-consuming.”

The Links acquired many of their machines from Minnesota, some refurbished from the cotton industry in the 1950s and others from the 1970s, and they bought some of the equipment from Brennan’s operation.

Start to finish on four pounds of wool, it’s about a two-week process, said Nicole Link, though the mill continually operates at various stages. She said 48 pounds of yarn can take up to a month to make.

Room for optimism

Eric Bjergso, general manager of the Canadian Co-operative Wool Growers, said the industry continues to deal with the after-effects of COVID-19 and global trade disruptions, which have meant a significant drop in demand and lower prices, “with a new crop always on the way.”

But although the market outlook is still bleak, Bjergso is confident conditions will improve. “We are already witnessing some change and a return to more stable shipping logistics, which is a positive sign,” he said.

He also believes wool, a naturally sustainable fibre that is comfortable, renewable and biodegradable, is regaining momentum as synthetics fall out of favour due to widespread concerns about pollution, including micro-particles that leach into oceans from laundry.

Lorraine Buchanan agrees. “I feel there’s so many problems with microplastics with all this clothing that maybe we will have to come back to wool and natural fibres,” she said.

As for Smith, who is starting to train her 12-year-old granddaughter in the craft of making Cowichan sweaters, she said a friend in Ontario who bought one of her Cowichan sweaters recently told her that her 99-year-old mother was in hospital and always feeling cold, but when she brought her the Cowichan, she felt better and happier.

“There is lots of healing in the sweater,” said Smith.