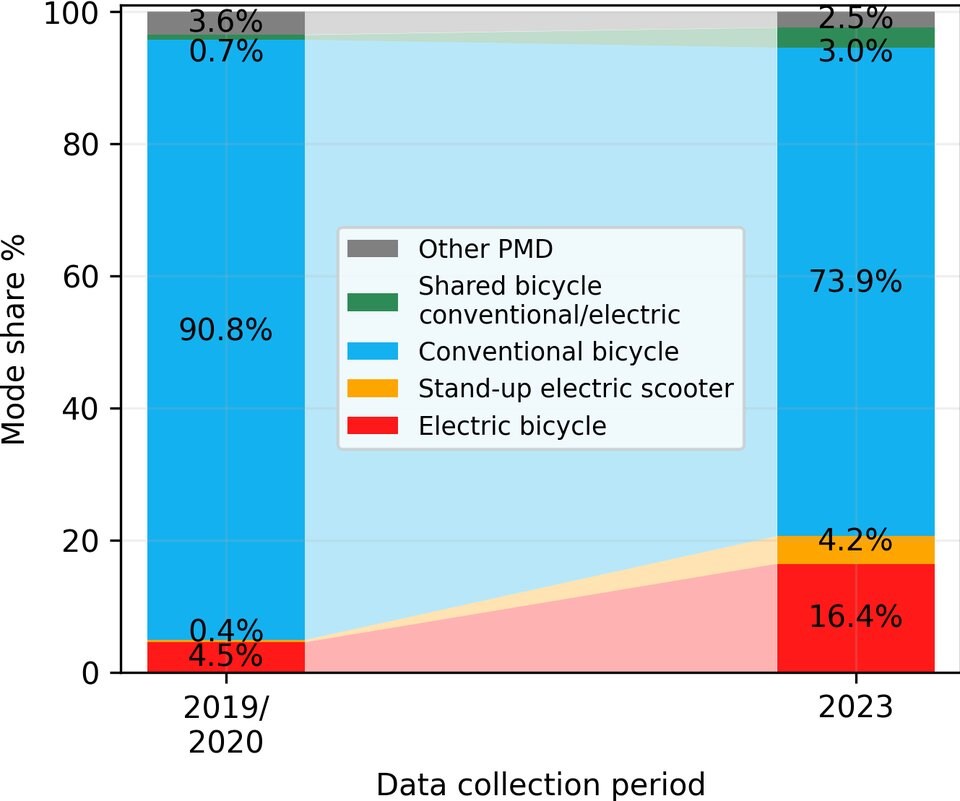

Electric bicycle use has exploded across Metro Vancouver over the past four years, quadrupling its share of riders compared to other personal mobility devices, a new report has found.

The — produced by the University of British Columbia’s Research on Active Transportation, or REACT, Lab — found the share of active transportation users who chose a traditional bicycle dropped to 74 per cent in 2023 from 91 per cent in 2019.

Over that same period, the share of riders who chose an e-bike climbed to 16.4 per cent from 4.5 per cent before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Alexander Bigazzi, an associate professor in UBC’s faculty of applied science and head of the REACT Lab, said their study shows bike and pedestrian paths across the Vancouver region have been clearly getting more motorized and faster.

“It’s been quite a dramatic change,” said Bigazzi. “It’s really rapid growth.”

Some e-vehicles speed up at 'alarming' rate

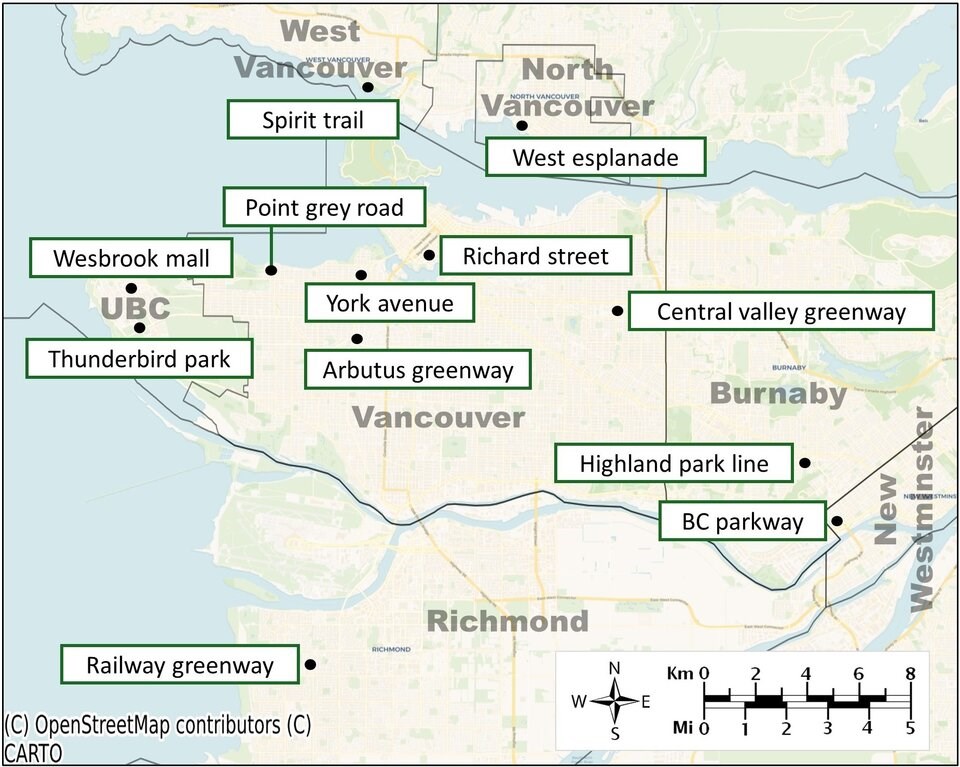

Bigazzi and his colleague used a combination of pneumatic tubes to measure vehicle speed and cameras to capture what kind of vehicle was passing by at 12 locations across Metro Vancouver.

Over the four years leading up to 2023, the average speed of off-street paths was found to climb 11 per cent.

Previous from the lab showed e-bikes weren’t going much faster than regular bikes. Now, Bigazzi says that difference is even smaller as legal e-bikes are equipped with limiters keeping speed below the 32-kilometre-per-hour limit.

鈥婱uch of the speed increases came from other devices. Electric skateboard speeds rose 4 km/h over the four years. Self-balancing unicycles, meanwhile, saw the biggest jump in speed, increasing by an “alarming” 10 km/h to a high-end average speed of 41 km/h, with nearly half exceeding 32 km/h, notes the report.

“That’s far faster than the other devices seen in this data,” said Bigazzi. “These are the electric ones, with someone standing over one wheel and kind of leaning forward.”

“The way they’re currently being used, they’re problematic.”

Stand-up electric scooters, meanwhile, saw a 10-fold increase in usage, with average speeds climbing to the provincial pilot program’s limit of 25 km/h, and often going over that.

“Speeds have been steadily going up,” said Bigazzi. “Roughly half are going over the limit.”

Bigazzi said their findings suggest a need for manufacturers and governments to work together to legalize more devices, and in the process, limit their top speeds to keep people safe.

“Because they’re not legal to operate, there’s no incentive to put a speed limiter,” said Bigazzi. “A lot of people don’t know what is legal, what is illegal, and what the speed limits are. I think that’s part of what has contributed to the problem.”

And while more needs to be done to educate the public, he said the trends showing a rise in personal mobility devices is a good thing for the region’s transportation system.

“They get people and out of cars. That’s good and we want to continue encouraging that,” he said.

Disruptive technology a risk and opportunity, says expert

Alex Boston, the former head of Simon Fraser University’s Renewable Cities program, said regulators have struggled to keep up with the wide range of micro-transportation options coming onto the market.

“Our sidewalks are being inundated with some of these disruptive technologies. They are a risk, but they can be an opportunity,” said Boston, who now runs his own urban consulting company.

Boston said that ultimately needs to come from the province and include an overhaul of B.C.’s Motor Vehicle Act.

“We see local government trepidatiously enabling certain micro-mobility innovation,” he said. “We have to get on an accelerated pathway.”

Boston, who rides mountain bikes in a club, said he has seen first-hand a rapidly rising interest in e-bikes. Of the 15 riders in his club, one had an e-bike at the beginning of the year. By the end of the summer, half the group had made the switch to electric.

“We’re talking about a 700 per cent increase in a few months,” Boston said.

Where in the mountains regulations are sparse, on the street, cities are trying to cope with the rapid introduction of new technologies — sometimes with great success.

E-bikes a model for other mobility devices

Bigazzi said the right mix of regulation and incentives can boost ridership while maintaining safe conditions. In Metro Vancouver, he and his colleague found the 30 km/h limit for electric bicycles still appears to be effective in keeping people comfortable and safe, and could even be bumped up to 32 or 35 km/h, the report concluded.

Even better, other research has shown the majority of e-bike riders did not transfer from normal bikes, but came as new users.

Overall, the results suggest the changes in speed over the past five years have reduced pedestrian comfort. However, the average path user, including pedestrians, was found to remain “moderately comfortable” with most mobility devices.

鈥媁hat’s required now, said Bigazzi, is a redesign of paths to better separate pedestrians and riders and open up especially congested areas. The report suggested wider paths be created in high-use and hilly areas, so personal mobility vehicles can safely and comfortably overtake slower riders.

Metro Vancouver’s rapid growth of riders turning to personal electric vehicles is only going to continue in the coming years — a change Bigazzi says is playing out on a similar scale across Canadian cities.

“It’s a faster fleet of vehicles we’ll be designing for. It’ll be busier and they’ll be more of them,” he said. “Inevitably, they’ll be some more conflict.”

“But hopefully there’s more of them.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story stated electric scooters travelled an average of 25 km/h, and therefore exceeded the provincial speed limit. This is incorrect as 25 km/h is now the new provincial speed limit. The study did, however, find many scooters exceeded that average and broke the speed limit.