Last year, Metro Vancouver set a target to expand its urban forests to cover 40 per cent of the region by 2050. But according to recently published data, that plan is already backsliding.

Between 2014 and 2020, Metro's tree canopy cover declined one per cent at a time the area covered by impervious surfaces spiked five per cent. The latest numbers, presented in a from Metro Vancouver staff, mean hard artificial ground now covers 54 per cent of the urban containment boundary (UCB), while only 31 per cent is covered by trees.

Pressures from growth, along with new provincial housing legislation, “will likely lead to further tree canopy cover losses and impervious surface increases,” write the authors of the report.

Jonathan Cote, Metro’s deputy general manger of regional planning and housing development, said the numbers weren’t surprising in a region growing as quickly as Metro Vancouver.

“We shouldn’t be throwing in the towel just because it’s difficult…” he said. “But I do think it is important for the region to recognize that right now, we are not trending in the right direction.”

For Alex Boston, an independent policy consultant and former executive director of the Renewable Cities at Simon Fraser University, the latest numbers in the Metro report mean any chances the region could meet its 2030 targets are now “blown out of the water.”

Boston and Cote agreed the province's housing legislation passed year will intensify development and and make protecting the region's trees canopy much harder.

“One of my big fears of this is this is a dramatic underestimate of what’s going to happen,” Boston said.

“We’re going to pay because our stormwater systems are going to need be increased in size to deal with the runoff. And we’re going to pay for it in lives.”

How trees buffer heat, clean water and prevent urban flooding

The report draws on data collected through satellite imaging and light detection and ranging technology (LiDAR), which creates 3D elevation maps by bouncing a laser from an aircraft to the ground.

Picture yourself as a bird. Below you, woodlands are broken up by roads, a housing development and a strip mall. Everywhere a tree’s leaves and branches stand between you and the ground counts as tree canopy cover — a measure scientists and governments around the world use to judge the extent of forests.

Working against tree canopy cover is a measure of the human urban footprint broadly defined as impervious surfaces. These are objects like paved roads, parking lots and buildings — anything that prevents or allows very little rainfall or runoff water to pass into the ground.

More hard surfaces mean an increased flood risk, disruptions to the water cycle and eliminating the ability of trees and plants to act as a buffer against flooding and filter water before it flows into streams.

Put more trees in a city and they will cool people and neighbourhoods with shade and evapotranspiration — a process where water is pulled through a tree’s roots, up its trunk and down its limbs. When that water reaches the leaves or needles, it vaporizes into the atmosphere, instantly dropping ambient temperatures.

In a well-treed neighbourhood, urban forests have been found to cool the surrounding environments by as much as seven degrees Celsius. But add more concrete and steel to that same neighbourhood, and it will absorb and radiate more heat. At a city-scale, all those hard surfaces boost temperatures through what’s known as the “urban heat island” effect.

As cities expand — building new industry, highrises and townhouses — the ability of an urban forest to cope and guard against the impacts of climate change is put to the test.

Coquitlam leads Metro with 4% decline in tree cover loss

By 2020, the report charts six-year declines in nearly every jurisdiction, save Lions Bay, which saw a more than six per cent jump, and Vancouver, Maple Ridge and the City of Langley, which saw increases of between 0.7 per cent and 1.4 per cent. Anmore, White Rock and the Langley Township held their canopy cover steady.

Coquitlam saw the largest decline in tree canopy cover, dropping four per cent, while West Vancouver, Burnaby and Tsawwassen First Nation registered just under three per cent slides, and the area covered by trees in West Vancouver dropped 2.5 per cent.

When it came to impervious surfaces, Lions Bay, Anmore and West Vancouver were the only ones to see declines, ranging from 5.8 per cent to 1.5 per cent. The biggest increases over the six years were in the Tsawwassen First Nation (27.7 per cent), and Richmond (8.8 per cent), Pitt Meadows (7.7 per cent) and New Westminster (7.1 per cent).

Boston said there are Metro municipalities whose rate of urban tree canopy loss has gone up even after they’ve introduced tree protection bylaws.

“These bylaws are just tracking tree loss. They’re not about protecting them,” he said. “We’ve essentially lost a small- to medium-sized municipality in trees.”

Erin Gorby, Coquitlam’s urban forestry and parks services manager, said part of the reason for Coquitlam’s larger decline in tree canopy is because it had more to start with.

“Even with our four per cent decline in canopy cover, we remain on the higher end of the spectrum, still ahead of 14 other member jurisdictions,” she said in an email. “Secondly, the City of Coquitlam is a high-growth city, and as such, experiences unavoidable pressures between tree retention and development.”

That’s especially true for Coquitlam, where development is happening in forested areas, she added. Gorby said Coquitlam is working to counter those pressures, has a plan to create a “compact urban area,” and is currently engaging with the public on a new urban forest management strategy meant to balance development with preserving the city's trees.

“Residents are accurate in their general concern about declining tree canopy cover because it is difficult to overstate the importance of trees, particularly in an urban environment,” said Gorby, adding Coquitlam's urban canopy “is still in very healthy ranges.”

Metro's staff report cites research showing fish and other river life face adverse affects when 10 to 20 per cent of a watershed has been covered by impervious surfaces. Nearly all of Metro Vancouver’s urban containment boundary has climbed past that point — with watersheds in Surrey, Delta, Richmond and the North Shore showing the highest artificial surface cover.

One solution: plant more trees

Pressure on the region’s urban forests comes amid the projected arrival of one million more residents over the next 36 years. Accommodating all those people is expected to require 500,000 new hosing units.

By 2050, the region is expected to lose 1,990 hectares of tree canopy. Some of those trees will be lost through the redevelopment of single-family housing into denser lots. More than two-thirds of the tree cover loss is expected to come from the expansion of low-density housing into “general urban lands.”

Over the next 20 to 30 years, the Metro report predicts tree canopy could drop to 29 per cent.

Metro staff say the only way to “offset” the losses and meet the mid-century urban forest target, would be through an accelerated push to plant new trees.

To counter a rise in hard surfaces and decline in tree canopy, the Metro Vancouver report recommends municipalities across the region set “ambitious” local tree canopy targets, monitor and report progress, and strength and enforce tree protection bylaws. They also call for tree canopy requirements in zoning bylaws.

Crucially, notes the report, planting should be done in a way that benefits vulnerable people in tree-scarce neighbourhoods.

Urban trees found to protect people, improve health

The report comes amid a growing body of research showing time among trees improves a number of ailments, from high blood pressure and heart and lung disease, to depression and anxiety. Studies in Metro Vancouver have linked children who live near green spaces with and .

In one of the most recent studies into the impacts of nature on human health, University of B.C. researcher Micheal Brauer found patients recovering from heart surgery are when they surround themselves with nature.

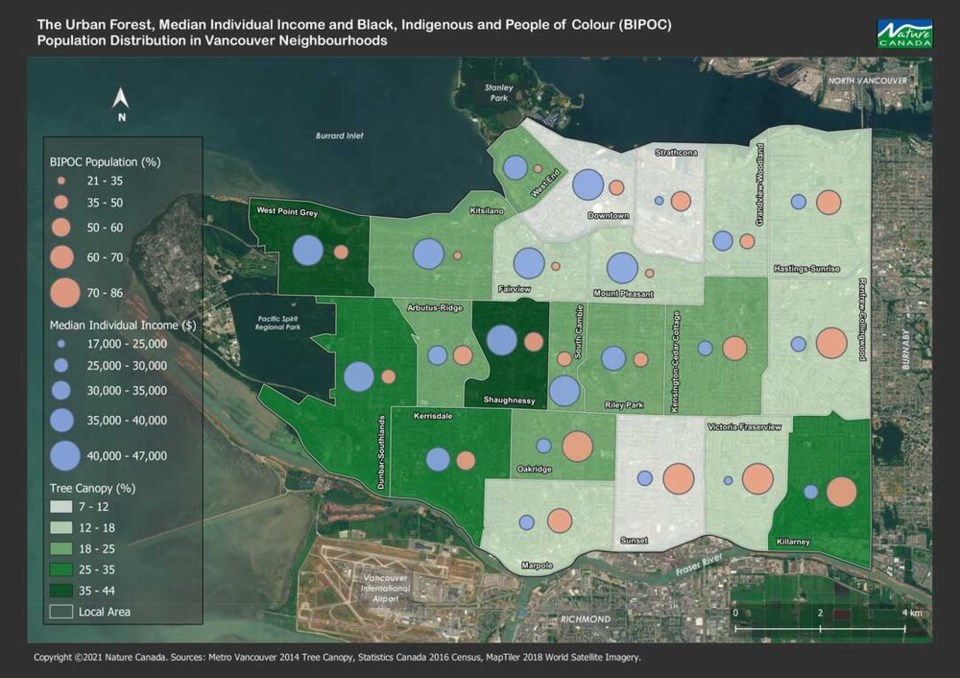

Across Canada, however, many cities see a stark divide between who gets to live among an abundance of trees and who does not. One 2022 study from Nature Canada found that across nearly all of the country’s largest cities, urban trees and their cooling effects are more concentrated in rich, white neighbourhoods.

In B.C., the report looked at the cities of Burnaby, Richmond, Surrey, Abbotsford and Vancouver. Nearly every city followed the same pattern: the more people of colour and lower the income, the fewer trees stand in a given city neighbourhood.

The pattern lined up with a Glacier Media carried out in the months after a record heat down scorched B.C. in June 2021. That reporting found that in some neighbourhoods with relatively little tree cover, like Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, emergency visits due to heat illness tripled relative to more affluent, treed areas.

A report from the BC Coroners Service later as a key long-term measure to prevent a repeat of the 619 lives lost to extreme heat in 2021.

The latest Metro report identifies a number of locations where the 21 members of the regional body could concentrate tree planting to rebalance those inequities. About 33,000 hectares, or 37 per cent of land inside Metro’s UCB, was found to qualify as potential planting areas.

That’s more than enough to accommodate the 9,900 hectares of trees required to offset the forecast losses while boosting urban forests to meet Metro’s 2050 target.

The Metro report says tree planting should prioritize high-density urban cores. Those include downtown Vancouver’s seafront, the Lonsdale area in North Vancouver, Richmond Centre and neighbouring areas, New Westminster, Surrey’s city centre, White Rock and the City of Langley.

Other areas highlighted for tree planting include:

- Tsawwassen First Nation

- Several areas of the North Shore from Dundarave to Ironworkers Memorial Second Narrows Bridge

- Burnaby

- A selection of residential areas along the Fraser

- Parts of Surrey such as Whalley, Newton and Guilford

- South and East Vancouver

“What it should be doing is telling us is ‘you’re unhealthy,’” added Boston. “The doctor has basically told us that you’re in trouble.”